On a tour of the new Yesterdayland: Innovations of the Past exhibit at the Willamette Heritage Center I found myself stumped by a set of small, slightly tapered, cylindrical artifacts on display with the question, “What is this?” The cylinders had large holes drilled through the middle with small screws offset on either side. One would easily fit into the palm of my hand. Next to the objects was a picture of a cow meant to be a helpful clue.

Cow horn weights WHC M3 1978-002-0003

As I stood mulling over the question and the objects childhood memories from visits to my grandparent’s farm came flooding back. Some, a little traumatizing. Scrambling up bales of hay in the barn, in order to be safe while Grandpa brought the cows in to feed. Running for the safety of the outhouse with cousins after being caught in the pasture as the noisy giant cows made their way to the barn. And let’s not forget the story of Soli, the bull. Meant to be a cautionary tale of how animals should be treated with respect, the story of the bull that turned mean and had to be put down was the stuff of nightmares, at least for a child.

But, back to the cow-related mystery objects in the exhibit. The simple cylinders seemed too short to be parts of a milking machine. And a cow would never have tolerated having them screwed onto such a tender part of their anatomy. What could they be? I gave up and lifted the flap to reveal the answer. The artifacts were horn weights.

Once a standard practice for breeding bulls, the weighted cylinders were locked into place using screws, on the end of horns to train them to curve downward. The weights varied depending on the age of the animal and the size of the horn. Training the horns with a downward curve made it easier for the animal to maneuver down a chute without getting horns caught and was also considered a preventative measure that would decrease injuries to the animal, others in the herd, and its handler. The weights were removed once the horns were growing in the desired direction. The practice is still in use today, though it has largely been replaced by sloping, trimming the tips of the horns.

This type of horn weight would have been used on the Rivercrest Jersey Farm, where my grandparents came to work after the end of World War II. My grandpa Boyd Fergus was the herdsman from 1945-1952. The farm was three miles southwest of Wilsonville along the road to Newberg that parallels the Willamette River. The farm was owned by an Englishman named Charles E. Couche, a wealthy media man from Portland.

Born in Exeter, England on April 4, 1890, Charles came to the United States via Canada in 1915 with his first wife Loana and two daughters, Eleanor and Gladys. The family settled in Portland where Charles opened an advertising agency and quickly earned a reputation as a brilliant media marketing man. One of his early contracts was with the Majestic Theater, executing their $40,000 advertising contract with Goldwyn Pictures for weekly movie promotions.

Oregonian, June 3, 1917

In 1918 Charles and local artist F.H. Clark took third place for their Liberty loan poster design in a hotly contested competition among the best advertising men in the seven western states region. Their poster, “The Prussian Brute” showed a German figure in the act of stealing a baby from the arms of its Belgian mother while in the background the Yankees are shown going over the top of the hill. His chief object, as quoted in the August 9, 1918 edition of the Oregonian was “to sell the war.”

He was also active with the local YMCA volleyball team, learned to drive and bought himself the latest model of the Scripps-Booth six touring car, planned local movie-themed balls and fundraisers, judged essay contests, and taught advertising classes. All this activity and community involvement cost him his first marriage in 1924 when his wife sued for divorce on the basis of desertion. After his divorce was final he married Myrtle Forbes.

In 1935 he saw a future in radio and took a job as the advertising and promotions director for radio stations KALE and KOIN. He continued to climb the ladder of success until he retired from the industry in 1947, as the general manager of KALE. It was about 1944 that the Couche’s decided to dabble in the dairy industry. Their talents were immediately put to use; Charles heading up the state club publication committee and Myrtle applying her talents as editor of the Oregon Jersey Review magazine.

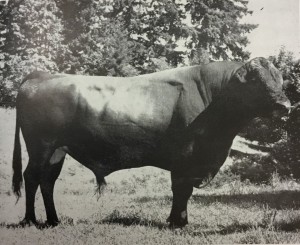

“King” Rivercrest bull 1946-1949. Jersey Review magazine, Fall 1949.

In 1945 they took a calculated risk in purchasing a yearling bull (Basil Stan Lilac Romulus King) from the C.W. Sherman stock farm in Scappoose, Or. He had an impeccable pedigree and within four years proved his worth by siring 23 daughters whose quantity of milk and percentage of butterfat per pound set new records. In 1949 he gained his 7-star rating, one of only eleven 7-star bulls in the United States at the time and was sold to Oklahoma A & M for the substantial sum of $2000 for use in their artificial insemination service. Never one to pass up a promotional opportunity, Mr. Couche launched an ad campaign benefiting Rivercrest Farm under the name “What One Bull Did for Us” and used it to promote and advertise not only his farm but increase the sales prices of the jerseys he sold.

Charles and Myrtle Couche (right) at home on the Rivercrest Farm with daughter Eleanor and husband Mike Rhodes. Courtesy of the Fergus family.

The Couche’s continued to work their influence on the state level sponsoring 4-H contests, hosting club picnics, organizing tours for visiting Jersey dignitaries for the yearly meeting culminating in what fellow Jersey members believed was the organization’s crowning achievement; a contract and ad campaign with Fred Meyer stores to sell milk and other dairy products made from Jersey milk under the All-Jersey trade name owned by the Oregon Jersey Cattle Association.

Between 1955 and 1957 Charles and Myrtle Couche began the process of retiring. Ending their work with the Oregon Jersey Cattle Association and selling their herd. They purchased a property management company in Lake Grove, OR where Myrtle kept the books and Charles, only semi-retired, turned his talents to the budding filbert industry and thoughts of nationwide promotion. He died in 1965, while Myrtle 6 years younger, died in 1982.

Cow horn weights. You never know what objects in an exhibit will connect you with your family history.

This article was written by Kaylyn Mabey for the Statesman Journal where it was printed 15 July 2018. It is reproduced here with sources for reference purposes.

Sources:

- Soli, Ferguys Family History blog, https://ferguys.wordpress.com/2018/08/05/soli/

- “A Sloping Science” Hereford World, March 2009, p. 36-38 https://hereford.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/SlopingScience.pdf

- RiverCrest Farm ad, Jersey Review, Fall 1949, State Library of Oregon, 636.22409795 Oregon

- <untitled> Oregonian (Portland, OR) 8 Aug 1952

- “New Setup at KALE” Oregonian (Portland, OR) 3 Aug 1944

- “Oregon Men Win Prize” Oregonian (Portland, OR) 11 Aug 1918

- “Jersey Bull Purchased by Oklahoma College” Oregonian (Portland, OR) 1 Jan 1950

- “Wilsonville Bull Wins Top Honor” Oregonian (Portland, OR) 28 Mar 1948

- “Ad Man Gains Inspiration for Copy in New Scripps-Booth Car” Oregonian (Portland, OR) 30 Mar 1919

- “Radio Station Men Lunch During Sessions” Oregonian (Portland, OR) 12 Oct 1940

- Obituary – Charles Couche, Oregonian (Portland, OR) 29 Jan 1965