by Richard van Pelt, WWI Correspondent

From the front page of The Daily Capital Journal:

SOCIALISTS MAY EXPEL THEIR LEADER

He Was the Only Member of the Reichstag to Vote Against Big War Credit

Berlin (via The Hague), Dec. 3. – Incensed because their parliamentary leader, Dr. Liebknecht, voted in the Reichstag Wednesday against the $1,250,000,000 additional war credit asked by the government, German socialists were talking today of expelling the doctor from the party.

Out of all the members of the law-making body, he cast the only negative ballot.

If the socialists did actually expel him, it was said Liebknecht would form a new anti-war party. That he would find a few followers, politicians agreed was quite likely, but speaking generally they declared the whole country was united for pushing the German campaign through to a definite conclusion.

Liebknecht would go on to be a leader in opposition to the war. His opposition led to revocation of his parliamentary immunity, removal from the Reichstag and to his imprisonment. At the end of the war, he joined with Rosa Luxemburg to found the new Communist Party (KPD). Along with Luxemburg he was murdered by freikorps military officers during suppression of the Spartacist Uprising in January, 1919.

On the Western Front the paper reported this headline:

THE ALLIES AGAIN TAKE OFFENSIVE IN WESTERN WAR ZONE

Both the British and French Armies Are Said to Be Heavily Reinforced

700,000 ALLIES ARE ON BELGIAN LINES

German Forces Also Strengthened and Great Battle Is Expected Soon

The editorial page criticized the parsimony of Salem residents in failing to contribute to Belgian relief funds:

WILL SALEM BE LEFT OUT?

Announcement that 6,000 tons of foodstuffs will be sent from Portland, Seattle and Tacoma was made yesterday by Samuel Hill, chairman of the committee appointed by Governor West to take charge of Belgian relief funds. Mr. Hill says a ship has been secured and that its name and sailing date will be made known soon. This is indeed welcome news to all who sympathize with the brave Belgians who have lost country, homes and everything in a war not of their seeking. The unfortunate situation of their country between two of the warring nations brought indescribable disaster upon them, and every generous America feels that he would like to relieve their distress as far as possible. It is too bad that no effort has been made in Salem to gather contributions to this cause, which may well be called “Holy.”

There are many here not only willing to give in this behalf, but really anxious to do so, and if no charitable institution or church will take charge of it, the mayor should name some one or have some arrangement made where contributions could be left. The little town of Dublin, in one of the New England states, through having a population of but six hundred, gave $2,800 to the Red Cross and other relief measures. At this rate, Salem would given nearly $100,000. Salem owes it to herself not to be unrepresented in this noble giving. It is not simply charity, but a duty we owe to humanity and the world. Who will take charge of the matter at once?

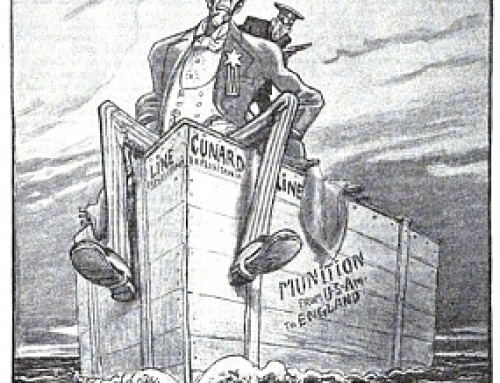

Several editorials written during these first months of war addressed the civilian crises that were taking place. Between the Thirty Years War and our Civil War, civilian populations were largely spared the effects of war. By 1914, defending urban spaces in a war fought over fronts that spanned hundreds of miles disrupted and dislocated populations in an entirely new way, made worse by technological advances that vastly increased this war’s destructive nature.

We would today call what the editorial addressed a humanitarian crisis. The term “humanitarian crisis” did not enter our vocabulary until approximately 1970. In an article, “The Disaster of War: American Understandings of Catastrophe, conflict and Relief” by Julia F. Irwin, published in First World War Studies suggests that what we thought about disasters and disaster assistance in the years prior to World War I determined how we viewed the significance of the war and the response we deemed appropriate. How and why we responded then affects how we look at disaster today (be it war, economy, or climate). Professor Irwin writes:

In the generation before the Great War, Americans increasingly began to conceive of catastrophes as phenomena that were, if not preventable, at least manageable, through rational human intervention. Moreover, the began to understand disasters as positive opportunities, occasions to sweep away outmoded infrastructures and to effect progress. At the same time, the period saw the birth and development of a disaster relief profession in the USA. When war broke out in Europe, many of the leaders in this emergent field became leaders in US humanitarian efforts as well. In this role, they transported the ideas and methods that they had cultivated in the wake of earthquakes, firs and other natural catastrophes to the battlefields of Europe. US war relief, in key respects, represented one facet of a much broader contemporary process of Americanization.

The Daily Oregon Statesman published an editorial addressing war hysteria:

HUMAN NATURE VINDICATED

It is with a feeling of immense relief that the American public, whose racial sympathies are struggling with its neutrality, sees discredited nearly all of the atrocity stories that filled the air for week after the war started.

The conflict today is quite black enough, with its pitiless slaughter and measureless harvest of misery. But nearly all trustworthy observers agree that it is being fought according to the rules of war, in a spirit of respect for the good opinion of mankind. War at best is brutal work, but the world by common consent honors the soldier when he is guilty of no superfluous cruelty or crime.

There were at first appalling accounts of the deeds of Germans, Belgians and French. Children had their hands cut off. Women were attacked and mutilated. Old men were massacred. Prisoners were tortured. It seemed like an outbreak of American Indian or Central African warfare in the midst of Christian Europe.

These stories have now been sifted, so far as they could be, and to the credit of human nature they are found to be almost wholly false, or at least unsubstantiated. Here is a calm estimate of them by Irvin Cobb, a trustworthy American newspaper man. It is from an article in the Saturday Evening Post, written after long and painstaking effort to get at the facts in the very places and among the very people concerned.

“My deliberate personal opinion,” says Cobb, “is that 80 percent of the stories are absolutely untrue. The remaining 20 per cent I have mentally catalogued in this way: Ten per cent were grossly exaggerated and 10 per cent approximately correct. At the same time let me add that, in a majority of instances, I am convinced the persons who peddled these hideous accounts of mutilation and torture and murder and rapine believed them to be true. The believed them to be true because they wanted to believe them.”

There we have it – about 10 percent of the stories may have been true, though perhaps nearly all of them were told in good faith, and all were printed in good faith by the newspapers, not as proved facts but as things alleged to be facts. Those soldiers who seemed monsters were really human beings like ourselves with probably no more cruelty or crime in their hearts that would be found among a similar number of men anywhere in civil life if they were plunged suddenly into a great and bitter war.

It may have been just as well, however, that the event of the atrocities was exaggerated. The very whirlwind of indignation that spread through the world had a salutary effect in softening the sternness of the Germans’ official attitude toward the Belgians, and checking any tendency toward unofficial cruelty in the rank and file of the various armies. All the combatants are now careful to avoid offending the conscience of mankind.

Atrocities did occur and atrocities were exaggerated. Atrocities, real or fictional, made for good propaganda. The exaggeration of atrocities, would come back to haunt Europe. Exaggeration of atrocities during World War I contributed to the failure of the allies to acknowledge or to pursue evidence of atrocities during the second phase of the war, which started in 1939.

Leave A Comment