by Richard van Pelt, WWI Correspondent

Sorting out the events of the first two weeks of the January, this is what a Marion County resident would have made of events:

Jan. 8—Allies gain north of Soissons, near Rheims, and in Alsace; French Alpine troops use skis in gaining an advantage in Alsace.

Jan. 9—Germans retake Steinbach and Burnhaupt; French take Perthes and gain near Soupir.

Jan. 10—French cut German railway lines to prevent reserves from coming to the relief of Altkirch.

Jan. 11—Allies, attacking from Perthes, are trying to cut German rail communications.

Jan. 12—French attempt offensive near Soissons and Perthes; they are checked in Alsace; British forces at the front are steadily increasing in number.

Jan. 13—Germans, reinforced, win victory at Soissons, forcing French to abandon five miles of trenches and to cross the Aisne, leaving guns and wounded; heights of Vregny are won in this fight by the Germans under the eyes of the Kaiser; Germans take 3,150 prisoners and fourteen guns in two days’ fighting.

Jan. 15—French are calm over the Soissons defeat; British gain near La Bassée.

What is taking place, from the perspective of a reader, is an example of the fog of war. The daily headlines report details that may only later make sense as the larger picture becomes clear. These headlines have been part of the First Champagne Offensive, which began in December of 1914 and would last until mid-March. For four months the French and British would fight along a line from the Belgian coast along the Yser to Verdun. The allies gained very little, attempting to go against a force of well-entrenched Germans. Casualties for the French and British would exceed 90,000.

Concluding his descriptions of conditions in the belligerent countries, Irvin Cobb describes the situations in Holland and Britain:

In Holland I saw the people of an already crowded country wrestling valorously with the problem of striving to feed and house and care for the enormous numbers of penniless refugees who had come out of Belgium. I saw worn-out groups of peasants huddled on railroad platforms and along the railroad tracks, too weary to stir another step.

In England I saw still more thousands of these refugees, bewildered, broken by misfortune, owning only what they wore upon their backs, speaking an alien tongue, strangers in a strange land. I saw, as I have seen in Holland, people of all classes giving of their time, their means, and their services to provide some temporary relief for these poor wanderers who were without a country. I saw the new recruits marching off, and I knew that for the children many of them were leaving behind there would be no Santa Claus unless the American people out of the fullness of their own abundance filled the Christmas stockings and stocked the Christmas larders.

And seeing these things, I realized how tremendous was the need for organized and systematic aid then and how enormously that need would grow when Winter came—when the soldiers shivered in the trenches, and the hospital supplies ran low, as indeed they have before now begun to run low, and the winds searched through the holes made by the cannon balls and struck at the women and children cowering in their squalid and desolated homes. From my own experiences and observations I knew that more nurses, more surgeons, more surgical necessities, and yet more, past all calculating, would be sorely needed when the plague and famine and cold came to take their toll among armies that already were thinned by sickness and wounds.

The American Red Cross, by the terms of the Treaty of Geneva, gives aid to the invalided and the injured soldiers of any army and all the armies. If any small word from me, attempting to describe actual conditions, can be of value to the American Red Cross in its campaign of mercy, I write it gladly. I wish only that I had the power to write lines which would make the American people see the situation as it is now—which would make them understand how infinitely worse that situation must surely become during the next few months.

“Illegal Boosting of Wheat and Flour Prices to be Probed” headlined the paper for this date. War in Europe and the failure of Australia’s crop “has made the world’s bread problem a serious one,” according to George Zabriskie, a representative of the Pillsbury Flour Company. He states that “if the nations of Europe continue to buy wheat at the present rate, America’s supply would be exhausted by March.”

The need for American flour has led to “between 75 and 80 percent of the surplus wheat in the United States

The article announced that the illegal price increases would be the subject of a federal probe and that “punishment will be meted out to any speculators implicated in any attempt to illegally advance the price of grain.”

Editorially, Minnesota’s non-partisan system was the subject for the day:

The state of Minnesota has a non-partisan legislature. It is the first of its kind that ever assembled in this country, and, therefore, its record will be watch with interest.

The news dispatches say that there is plenty of evidence of a determined effort to go back to the party system and tell of a recent “harmony” meeting of republican leaders holding this view. Organization men in both the old parties are working to discredit the non-partisan plan, and contend that party organizations are necessary to the success of popular government.

* * *

What state necessity exists for [parties]? What good are they but to keep one set of men in and the other out of office?

A great many persons outside of Minnesota are asking these same questions, and awaiting satisfactory answers. That fact makes the Minnesota experiment of unusual interest to the who nation.

In Europe, the Battle of Soissons, which started.on the 8th was not going well for the French.

The headlines tell the story:

Success of German Drive in Northern France Continues

French War Office Says That Many trenches Have Been Captured

Germans Claim Capture of More Big Guns at Soissons Today

French Loss East of Soissons Greater Than First Admitted

“The French defeats east of Soissons is more serious than Paris officials reports indicate, but not so overwhelming as Berlin’s comparison of the situation suggests. Instead of a loss of five miles of territory which the French acknowledged they suffered, more than 10 miles of front changed hands” J. W. t. Mason reports from United Press.

Reporting from Paris, William Phillip Sims, writing for the United Press, wrote:

The success of the Germans in their new drive in northern France continued, according to the official statement issued by the war office this afternoon.

It was admitted that the enemy had recaptured a line of tranches at Notre Dame Lorette, near Cerency, which were taken by the French earlier in the week. The german attack at that point was pushed with the utmost determination until the French finally abandoned the positions.

During war, a soldier’s humor can be mordent as an article entitled “British Solders Learn To Make All Sorts of New-Fangled Dishes”:

“We are learning to make all sorts of fancy dishes that would make a fist-class menu for any hotel,” writes Corporal T. Harper, of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry in a cheery letter home. “Have you even tried Jack Johnson soup? This is how you make it. You get the usual stuff in a pot, and get it on to boil just within range of the German guns. By and by a “Jack Johnson” shell comes along and drops into your soup serving out the contents very liberally among all who happen to be near enough whether then said they were going to skip the soup course or not.

“Then there’s ‘Coal-box cutlets.’ You get a tin of bully beef, and you cut a few strips with any old knife, you an lay your hands on. You put the beef on a slice of bread, and before you have time to look around, a ‘coal-box’ shell drops on you and your beef is nicely seasoned, if it is still there, or you are able to take any further interest in beef. We make a specialty of nice shrapnel teas. What you do is light a fire and set water to boil in your billy can. When it is nicely a boil the smoke from the fire attracts the Germans and their guns begin to drop shrapnel all over the place. Just as you are going to raise the can to your mouth to take a big drink of tea a shrapnel bullet drops into it, and you are lucky if you haven’t a call to make on the regimental doctor or undertaker.

All this makes meal times very much exciting and entertaining as at home, so you will have to start an association, for brightening up meal times unless you want us to be terribly bored when we get back.”

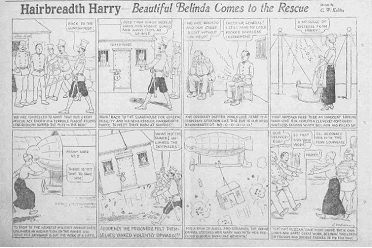

Even the cartoons related the war:

Leave A Comment