By Richard van Pelt, WWI Correspondent

In Vienna, the German Ambassador Tschirschky urges Austria to quickly attack Serbia, before Russia can intervene. Encouraged, an Austrian official comments “We are completely one with Berlin.”

In the Hungarian assembly in Budapest, Tisza makes a somber speech on the situation with Serbia. Hungary, with a substantial Slavic population, did not want a conflict with Serbia that could foment nationalistic feelings among Slavs living in Hungary.

In Germany, the chancellor, Bethmann-Hollweg hoped that the crisis will divide the Entente, which consisted of Britain, France, and Russia.

In Britain, the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, warns Russia and France that the Serbian crisis could lead to war, telling Russian Ambassador Benckendorff that the possibility “makes my hair stand on end.”

These were tiny temblors, low enough not to make the news, but which will grow in intensity until they dominate the front pages. Front page news in Salem for the day addressed revolution in Mexico, allegations that Teddy Roosevelt was a fake explorer, union shops, and anarchists as martyrs:

FEDERALS BEATEN TO A FRAZZLE

Undertook a Surprise But Were Themselves Ambushed and Whipped

REBELS CAPTURE IMMENSE STORES

Battle Will Hasten Heuerta’s Flight, as Way to Capital is Practically Open

Mexico was in the fourth year of a revolution or civil war that would last for most of the decade. During several points in the struggle, the United States would intervene, diplomatically or militarily. In 1914, President Wilson ordered troops to Veracruz to prevent the illegal shipment of arms to the combatants. In 1916, responding to Pancho Villa’s raid on Columbus, New Mexico, and the death of 16 United States citizens, Wilson sent forces under John J. (Black Jack) Pershing into Mexico to capture Villa. The campaign would not be successful, and the interference contributed to a growing anti-American sentiment by many in Mexico.

Brands Roosevelt As Fake Explorer

Charging that a river Roosevelt claimed to have discovered, was already spanned by a bridge and telegraph wires, Henry Savage-Landor said that “Roosevelt first claimed he discovered the river and then admitted that he crossed that river on a bridge spanned by telegraph wires.”“Rome,”he said, “has the right name for Roosevelt. They call him ‘Pallonaro,’meaning literally ‘one who inflates toy gallons with gas.’” The river, now known in Roosevelt’s memory as Rio Roosevelt, is located in Brazil and flows into the Amazon. Formerly known as the River of Doubt, Savage-Landor charged that Roosevelt “has copied some of the principal incidents of my voyage. He even had the same sickness and injuries. These things often happen to big explorers who carefully read other travellers’ books.”

1914 was an active year for American labor, and the right of workers to organize. The right to organize would be enshrined later in the year in provisions of the Clayton Antitrust Act:

The labor of a human being is not a commodity or article of commerce; nothing contained in the antitrust laws shall be construed to forbid the existence and operation of labor organizations… nor shall such organizations or the members thereof be held or construed to be illegal combinations In restraint of trade under the antitrust laws.

Labor issues were a front page article, describing the efforts to unilaterally create open shops in Stockton, California:

SOWING THE SEED FOR TROUBLE WITH ALL UNION LABOR

Merchants, Manufacturers and Employers Association of Stockton Start It

DECLARE THEY WILL MAINTAIN OPEN SHOP

More than 200 Men Working in Planing Mills Walk Out After Announcement

The fight for the open shop was on today in Stockton.At a meeting of the Merchants’, Manufacturers’ and Employer’s association, held last night at the Hotel Stockton, it was decided to inaugurate the open shop rule at eight o’clock this morning. It was stated that the 332 employing firms affiliated with the association voted unanimously on the proposition.

The first evidence of a fight become manifest this morning in the planing mills when the proprietors of the four large mills called their men together and informed them that henceforth the mills would be conducted on the open shop plan, that men would be engaged without reference to union affiliations, that the union label would be abolished and that union stewards would not be permitted in the mills. The men were told that the same hours and wages would be maintained and that all men who cared to remain could do so and that those who did not care to do so could call at the offices and get their pay. The men remained true to their union principles by quitting their jobs. About 200 mill men went out.

Labor issues figured prominently in the news during 1914. In April, at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, owned by John D. Rockefeller, there occurred The Ludlow Massacre:

The date April 20, 1914 will forever be a day of infamy for American workers. On that day, 18 innocent men, women and children were killed in the Ludlow Massacre. The coal miners in Colorado and other western states had been trying to join the UMWA for many years. They were bitterly opposed by the coal operators, led by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company.

Upon striking, the miners and their families had been evicted from their company-owned houses and had set up a tent colony on public property. The massacre occurred in a carefully planned attack on the tent colony by Colorado militiamen, coal company guards, and thugs hired as private detectives and strike breakers. They shot and burned to death 18 striking miners and their families and one company man. Four women and 11 small children died holding each other under burning tents. Later investigations revealed that kerosine had intentionally been poured on the tents to set them ablaze. The miners had dug foxholes in the tents so the women and children could avoid the bullets that randomly were shot through the tent colony by company thugs. The women and children were found huddled together at the bottoms of their tents.

The Baldwin Felts Detective Agency had been brought in to suppress the Colorado miners. They brought with them an armored car mounted with a machine gun—the Death Special—that roamed the area spraying bullets. The day of the massacre, the miners were celebrating Greek Easter. At 10:00 AM the militia ringed the camp and began firing into the tents upon a signal from the commander, Lt. Karl E. Lindenfelter. Not one of the perpetrators of the slaughter were ever punished, but scores of miners and their leaders were arrested and black-balled from the coal industry.

A month following the massacre the front page headline read:

LUDLOW’S STORY IS TO HORRIBLE TO PUT IN PRINT

Details Equalled Only by the Burning and Sacking of Ancient Rome

Colorado Sitting On Volcano’s Edge

Father Saluted With Child’s Corpse When He Went to Militia Camp“The true story of what transpired at Ludlow is too horrible to print,”said Judge Ben Lindsey here today.

“The details of the Ludlow affair are almost unbelievable,”said Judge Lindsey. “They are equalled only in there stories of the sacking of Rome, the pillaging of Carthage and the inhumanities of the Balkan war.

“Colorado is sitting on the edge of a volcano. If federal troops are withdrawn there will be a war of reprisal too horrible to contemplate.

“The Ludlow story is a black mark on the nation’s history. I can only suggest it and fill in the outlines with the direct testimony of those women who have suffered.”

Anarchists made the front page as well:

ANARCHISTS INSIST DEAD ARE MARTYRS

Local Anarchists Determined to Make Demonstration When Victories (sic) of Bomb

Explosion Are BuriedRegardless of the police, it was announced today that local anarchists will pay a tribute, at a meeting in Union Square Saturday, to the four of their number killed by the Fourth of July bomb explosion in a Harlem tenement house.

They persisted in their view that the bomb was planted by capitalistic enemies of their movement and that its victims were martyrs to the cause of anarchy.

Anarchists were active in Oregon and the Northwest in the years preceding the First World War, as described in the Oregon Encyclopedia:

From 1895 to 1897, a group of farmers in Sellwood, a town on the Willamette River southeast of Portland, published an influential anarchist newspaper. The masthead of the Firebrand, a weekly publication, proclaimed its mission: “For the Burning Away of the Cobwebs of Ignorance and Superstition.”

Unlike many anarchist publications in an era during which they proliferated, the Firebrand tackled social issues as well as politics. It proposed, for example, radical changes in relationships between women and men. In addition to reporting news about local anarchist communists and promoting free love, it also published critical responses to Herbert Spenser’s Principles of Sociology, reported on the impending release of Oscar Wilde from prison, and ran stories on the actions of the Catholic Church in Spain.

There were other anarchist links, closer to home, to Scio, to Emma Goldman, and even to Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh.”

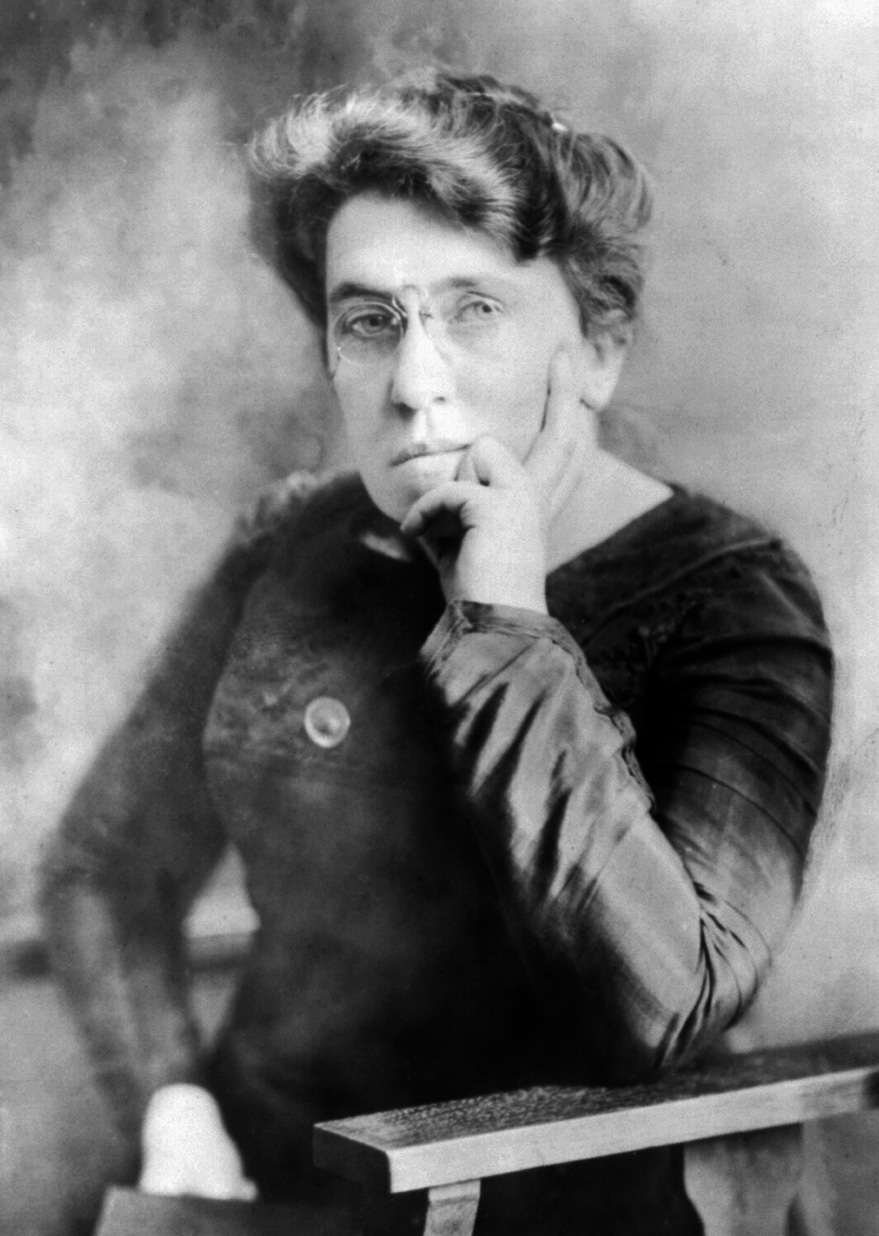

Emma Goldman. Source: Wikipedia.

Emma Goldman was a prominent anarchist, speaker and writer. She describes, in an article in Mother Earth, her visit to Scio and to the home of Gertie Vose:

Eighteen years ago I made my second lecture tour to the Pacific Coast. While in Oregon I was invited to Scio, Oregon, a small hamlet. The comrade who arranged the meeting and with whom I stayed while in Scio was Gertie Vose.

I had heard of Gertie through the pages of Fire Brand and Free Society, from a number of friends, and a few letters exchanged with her. As a result I was eager to meet the woman who, in those days, was one of the few unusual American characters in the radical movement. I found Gertie to be even more than I had expected, —a fighter, a defiant, strong personality, a tender hostess and a devoted mother. She had with her at the time her six year old son, Donald Vose. Another child, a girl, lived with her father, a Mr. Meserve, from whom Gertie had separated.

The stress and travail of life interrupted a correspondence which was a great inspiration for a number of years after my visit. But I knew Gertie Vose had taken up land in the Home Colony at Lake Bajr, Washington, and that her son was with her: that she continued to be the fighter when the occasion demanded. Between 1898 and 1907 I did not get to the Coast and when I finally revisited the Home Colony about six years ago, Gertie Vose was away and so was her son.

Donald Vose did not share his mother’s anarchist values. He was “turned,” to use an intelligence expression, by William J. Burns and was implicated in the conviction of the Los Angeles Times bombing of 1910. In “The Iceman Cometh,” Vose is portrayed as the character, Don Paritt. In a revival of the play, this is how he is described by O’Neill in an article in The New York Times :

Don Parritt is among the more complex characters O’Neill drew. He is based partly on a 24-year-old man who figured in a sensational newspaper story of the period — treacherous Donald Vose, son of Gertie Vose, who was a member of the anarchist Home Colony near Tacoma, Wash., which advocated the violent overthrow of capitalism and all governmental restriction of individual freedom.

The story of Vose’s villainy, which O’Neill had followed, began in 1910 — the result of a continuing enmity between the Structural Iron Workers Union of America and the employers’ coalition known as the National Erectors Association.

The iron workers had been planting bombs on the West Coast in retaliation for the employers’ anti-union tactics, such as fierce opposition to the closed shop and the dismissal of union sympathizers.

The outcome was a bitter class struggle, with The Los Angeles Times relentlessly attacking the union in its editorials:

On Oct. 1, 1910, at 1:07 A.M., a suitcase containing 16 sticks of dynamite exploded in a narrow space, known as Ink Alley, behind The Los Angeles Times building; it started a fire that trapped 21 machinists and other workers, who died of suffocation. The Times accused members of the iron workers union of having set the charge.

The city of Los Angeles hired the private detective William J. Burns to hunt down two union agitators, brothers named James B. and John J. McNamara. During a trial in which they were defended by Clarence Darrow, the McNamaras pleaded guilty, as part of a bargain to avoid the gallows, and were sent to San Quentin — James for life and his younger brother for 15 years.

Detective Burns believed that two other men — Matthew A. Schmidt and David Caplan — were as culpable as the McNamaras. For three years he hunted them, but they eluded him.

Among his surveillance targets was the anarchist colony in Tacoma, where he marked Gertie Vose’s son, Donald, as weak and disaffected, and offered him $2,500 to turn spy. Donald accepted the bribe and, on Burns’s instructions, asked his mother to write to her old friend Emma Goldman, saying she was sending him to work for the movement in New York.

Burns and Goldman had long been sworn enemies. She had disparaged him in her magazine as “a sneak” who “could not apprehend a flea.” Burns, in turn, had denounced Mother Earth as “the central power station” of the anarchist movement. He would have liked nothing better than to trap Goldman — along with Schmidt and Caplan.

Goldman mistrusted Donald Vose on sight, later recalling (in Mother Earth) her dislike of his “high-pitched, thin voice and shifting eyes.” Echoing her words, O’Neill described Don Parritt in “The Iceman Cometh” as having an “unpleasant” personality, due to “a shifting defiance and ingratiation in his light blue eyes.”

Emma stifled her aversion, however, because “he was Gertie’s son, out of work, wretchedly clad, unhealthy in appearance,” and she offered him shelter.

Schmidt finally turned up and Vose led him into the trap prepared by Burns. He was arrested, as was Caplan, a few days later.

“At once we realized that Donald Vose was the Judas Iscariot,” wrote Goldman. “It was Donald Vose who cold-bloodedly, deliberately betrayed the two men.” Goldman was especially incensed, she wrote, “because of the mother of that cur; terrible because he had grown up in a radical atmosphere.”

O’Neill, imaginatively carrying the Vose story beyond the facts, created in Don Parritt a man who has betrayed his mother (rather than her comrades) to “the Burns dicks,” as he describes them in “Iceman.”

Something in Vose’s circumstances and personality happened to resonate with O’Neill’s own background, and it is not difficult to find emblematic traces of O’Neill’s younger self in the character.

In the play, Parritt turns up at Harry Hope’s, apparently seeking absolution from his mother’s former lover, Larry Slade. He finally confesses that he betrayed his mother out of a long-suppressed rancor toward her, a rancor not unlike the submerged hostility O’Neill bore his own withdrawn and neglectful mother — and upon which he dwelt in “Long Day’s Journey Into Night.”

In her 1916 essay, Emma Goldman lays a curse on Vose:

Donald Vose you are a liar, traitor, spy. You have lied away the liberty and life of our comrades. Yet not they but you will suffer the penalty. You will roam the earth accursed, shunned and hated; a burden unto yourself, with the shadow of M. A. Schmidt and David Caplan ever at your heels unto the last. And you Gertie Vose, unfortunate mother of your ill-begotten son? My heart goes out to you Gertie Vose. I know you are not to blame. What will you do? Will you excuse the inexcusable? Will you gloss over the heinous? Or will you be like the heroic figure in Gorky’s Mother? Will you save the people from your traitor son? Be brave Gertie Vose, be brave!

Leave A Comment