by Richard van Pelt, WWI Correspondent

The headlines from the Capital Journal graphically describe the fury of battle and warn Americans “to travel at their own risk:”

ANGRY BULLETS ZIP AND SING IN TRENCHES – MEN LIKE GHOSTS

Machine Guns Rattle and Spit Stream of Fire At Dim Shadows While Illuminating Fuses Hang Suspended Over Weird Battlefield – Like Behind Scenes For Theatrical Performance

By William Philip Simms

With the French Army, April 11 – Up over the hill we stumble through the darkness. Ahead is our guide, the captain of the general staff. Suddenly the ridge ahead is sharply outlined against a brilliant light far on the other side. You clearly distinguish the outlines of a trooper coming toward you. What seems to be a cow is a patch to the right. There is another house and some outbuildings. Then the light dies out. It was a fusee, an illuminating bomb, shot into the air by one side or the other to light up the landscape and prevent surprise attack.

Now you hear the pop of the rifles, not a confused crackling without cease intermission, but a pop, pop, pop, pop, with definite intervals. Sharp-shooters all along the line are shooting at anything they see moving – or think they see. Then you hear the rattle of a machine gun. It lasts for less than 10 seconds. The gun server has turned the crank but a round or two, perhaps a shadow that moved when that French fusee began to fall over there in his direction. The German fusee is shot up into the air by a special gun like a revolver with a large barrel. The French goes up with a skyrocket and burns with a beautiful, opalescent, bluish light. The German light is more yellow.

At the foot of the hill you find yourself in a sunken road. And you are immediately glad that it is sunken. Suddenly there is a fusee light, you see everybody duck their heads as simultaneously you have ducked yours. It was all over before you realized what it was all about. For an instant you thought that it was an angry bumble bee jabbing at your ear. Sheepishly you realize that it was a bullet. You are getting close. One more turn to the right and you find yourself in a shallow trench, about waist deep.

The trenches zig-zag like a whole flock of z’s strung together, getting deeper as you go along. The z’s protect you to the maximum no matter from which direction the bullets come. You pass the outlines of a cross seen against the fusee’s light, the grave of a soldier at the end of a trench. You look and see several buried there held partly in place by stakes and woven brush. These and the angry zip of bullets are not encouraging.

Suddenly a sharp bang right at your elbow acquaints you with the fact that you have arrived. A solder has just fired and you are in the front trenches. The Germans are only 20 yards away and you can hear them pelting away at you. And soon you can tell the difference between the snap of the German mauser and the softer crack of the french rifle. The men wear a hood of waxed canvas over their heads and in the stillness, broken only by the pop of the rifles they seem more like ghosts than humans trying to kill others of their species. Both sides listen – listen – anxious to catch the whispered word that will tell where or when to throw the explosive hand grenade.

The night is without sound save for a muttered oath when some one slips in the mud, and the noise of the rifles. It seems like a party or as if you were behind the scene at a theatrical performance. You feel quite safe. You have already forgotten that grave back there.

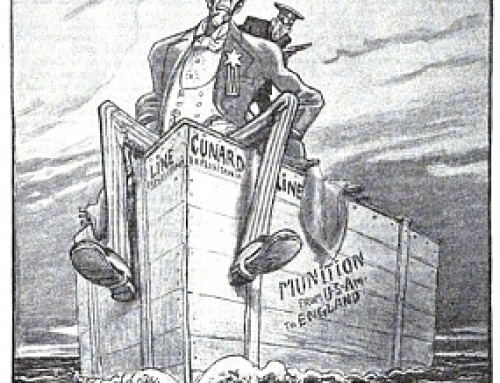

As events in July of 2014 demonstrated, travel during times of conflict carries with it risks, whether at sea or at 37,000 feet aboard civilian transport. In 1914 the ocean was just as likely to be a combat zone as any trench in Flanders:

AMERICANS WARNED THAT TRAVEL IS AT THEIR OWN RISK

Washington, May 1 – A warning from the German embassy that Americans sailing for Europe must travel at their own risk today promised a greater sensation than any previous communication that has come from the Imperial government’s official headquarters in this country since the war opened.

Prince Von Hatzfeldt, counsellor of the embassy, explained that Ambassador Von Bernstorff prepared the “notice” printed in all New York papers himself. Whether the advertisement was published at the order of his government was not stated.

Americans Are Warned

“The warning is given so that Americans may avoid trouble,” said the counsellor. “The first warning of Germany’s submarine blockade was given on February 1 and this is simply a repetition of that warning. The purpose is to let Americans know that when sailing they had better do so under their own flag.”

Asked if the warning was intended to convey an impression of increased danger, Prince Von Hatzfeldt answered negatively, saying “this is merely another warning.”

Leave A Comment