by Richard van Pelt, WWI Correspondent

The business of trade, free speech, and politics was the subject of a column by Miriam Russell:

FREE SPEECH AND TRADE SERVICE

I walked along a commonplace business street this morning with my mind occupied partly with the getting done of a large number of errands in a short length of time, partly with an absent wonder that business streets should be so ugly. Long successions of cheap, drab little stores mark the trade street which is to be found running through every residence section of a big city. Why couldn’t there be a strip of grass, and decent architecture, and why were printers so dilatory – oughtn’t I make time for –

I stopped with pleasure in front of my grocery. Here at least were people with a little sense of symmetry and beauty! The German love of growing things found vent in the most delightful arrangement of asparagus with strawberries, dark what cress and white Bermuda onions. Never had radishes looked so crisp and crimson, the spinach so green, the butter beans so yellow. There were baskets of pansies and pots of mint. I stood and looked about and sniffed the spicy air with sheer joy. And best of all, there were two men ready at once to wait on me. Wonder of wonders in that usually busy place where women are wont to take their turns, three or four in line awaiting each salesman’s attention!

Not even did I have to wait at the delicatessen counter for my pink boiled ham. I will not buy cooked food at the usual delicatessen store, but that delightfully clean counter has captured me. The white-coated, clean-handed Teuton slicing up celery as if it were a religious rite, or beating mayonnaise with perfectly fresh eggs and perfectly good oil in a perfectly clean bowl, the sparkling steel of the ever-sharp mechanical slicer – they’ve won me over. I believe in ready made food when it’s prepared like that.

I noted, still absently, that the proprietor seemed to have an air of absorption. I felt with a slight surprise a touch of nervous asperity in the speech of the bookkeeper. But everyone has off days, especially at the beginning of warm weather, and I thought no more about it.

Then I stopped in at the home of a friend. Observing that I carried some groceries she asked: “Do you still trade at Ruhmsottel’s Most everyone in the neighborhood has stopped.”

“Why? They are far and away the best for miles.”

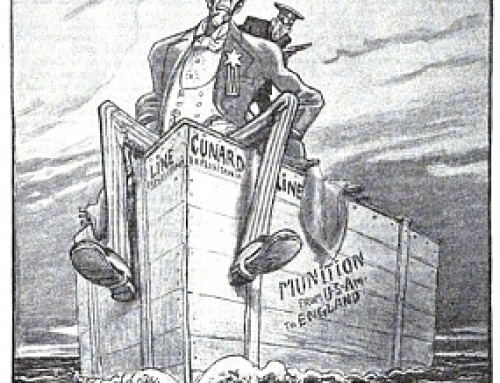

“Yes, I know. But you see they approve of the sinking of the Lusitania, and the people around here won’t stand for it.”

I nearly burst with indignation. When I could speak I ejaculated:

“But I’m an AMERICAN. Do you mean to say these people actually boycott the best tradesman, the cleanest, most competent, who give the most intelligent service, simply because they don’t agree with his political views?”

“Why, certainly. Those Dutchmen were all chuckling over the Lusitania affair, and I say it serves them right to lose their trade.”

I remembered the absorption, the asperity, the empty store. And I came home reflecting on the difference between hasty passion and fixed principles.

Now, I haven’t any words strong enough for the wickedness of the Lusitania affair. But I haven’t got two hundred and ninety-five years of American ancestry back of me, with its ingrained principles of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of political opinion only in the hundred and ninety-sixth to stop buying spinach from a man who thinks otherwise than I do.

If my grocer should stop procuring and arm against my country I should, if opportunity offered, go out in person and kill him with great joy. But so long as he says quietly at home giving me good service in his own profession, whether or not he thinks black is white, that Germany was justified in sinking the Lusitania, that the moon is made of green cheese, that baptism by immersion is necessary to salvation, or that New York city is a desirable place in which to bring up children is none of my business as a customer.

The next step to boycott for political disagreement is the abolition of freedom of speech. An American who stops to think two minutes about the principles of Americanism will realize this.

It is just possible that the German grocer gloated disagreeably to his customers. If so, that was a bad error of taste. It should have been met with a sharp rebuke.

But so long as any man or woman meets another on a ground of common interest, whether it be the grocery trade or an afternoon tea, in any jAmerican spot, the common interest and the participators therein are American. Let them argue of they will, over any subject under heaven. But let them remember that to punish another for his private belief is to violate the most sacred principles of American liberty.

“But let them remember that to punish another for his private belief is to violate the most sacred principles of American liberty.” Overarching principles are meaningless in a world where passion and ideology rule: “But I haven’t got two hundred and ninety-five years of American ancestry back of me, with its ingrained principles of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of political opinion only in the hundred and ninety-sixth to stop buying spinach from a man who thinks otherwise than I do.”

Leave A Comment