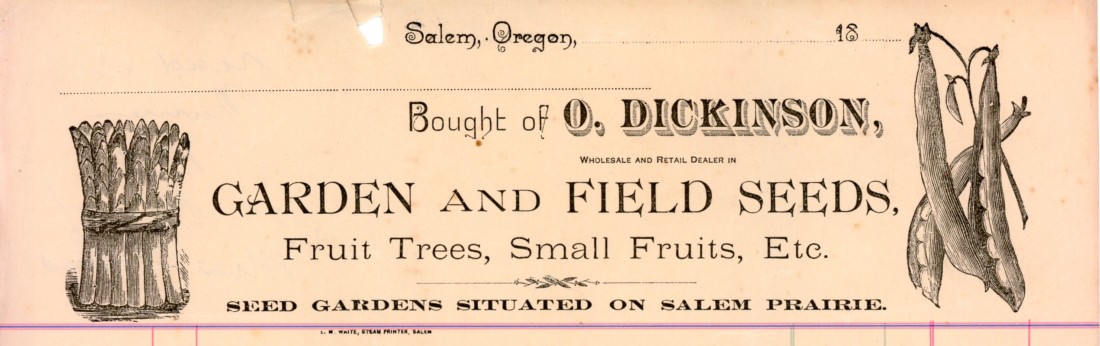

I have found there is an almost eerie phenomenon that happens working in an archive – the tendency for tiny scraps of history to appear at choice moments and provide a big dose of timeliness and context for my own understanding and processing of current events. Such was the case for me earlier this month. While putting away a series of handwritten speech notes from a local Woman’s Christian Temperance Union member, the backside of a scrap of paper used as an envelope for the bundle caught my eye. Neat illustrations of asparagus and beans decorate letterhead for an “O. Dickinson, Wholesale and Retail Dealer in Garden and Field Seeds, Fruit Trees, Small Fruits, Etc. Seed Gardens Situated on Salem Prairie.” This seemingly inconsequential piece of scratch paper stood out to me as a reminder and a witness to a poignant story of community.

Obed Dickinson was not always a seed merchant. Far from it. His first calling in life was as a Congregational Minister. After graduation from a theological seminary in Andover, Massachusetts, he and new wife Charlotte sailed around the tip of South America on a four-month journey to become missionaries in Oregon. They arrived in Salem in 1853 and began their work pastoring a small church.[1] Church for the Dickinsons at this time meant a gathering of people rather than a building. The congregation met first in a small schoolhouse near Marion Square, and then in a retrofitted shop that had been moved to the SE corner of Liberty and Center Streets – about where the old Nordstrom’s entrance to the Salem Center stands today.[2] The church would meet in that repurposed building for nearly a decade before building their own church structure at that site.[3]

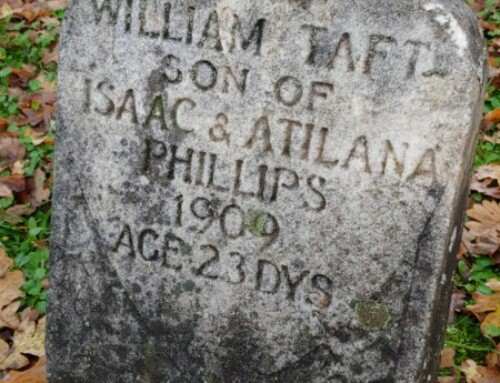

The church family was small. By 1859, boasting only 24 members.[4] By that time Dickinson was also fostering a new church ¼ time across the Willamette River in Eola.[5] Oregon had just been admitted as a free state to the American Union during the intense pressure of political events that would lead up to the Civil War. While being a free state sounds like a laudable thing – it did outlaw slavery — the framers of the state constitution had done so with an exclusion clause which stated: “No free negro or mulatto, not residing in this State at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall ever come, reside, or be within this State, or hold any real estate, or make any contract, or make any suit therein…”[6] It goes on to direct the legislature to allow public officials to remove any black person found in the state and to punish anybody caught employing or harboring them. Even if the laws were rarely enforced, the net effect was a strong message that black people were not welcome in Oregon.[7]

This message was also evident in the actions and words of many people in the city of Salem as reported by Rev. Dickinson in correspondence. His pointed criticism of and preaching against an incident of extrajudicial brutality against a black adolescent later found innocent of a crime[8] and unequal educational opportunities for students of color[9] have disturbingly familiar echoes in today’s headlines, despite the passage of time and many reforms.

Issues came to a head between Dickinson and a deacon of the church, who happened to underwrite a large portion of the pastor’s salary. In writing to the missionary board in 1862 describing the conditions that made it difficult for him to pay his dues, Dickinson noted that his detractors said of him: “I am stubborn because I would not yield to their counsel of having a separate meeting for the blacks to join the church. I am stubborn because I maintain the rights of the blacks to an education for their children, against the popular opinion of the place. I am stubborn because I set myself firmly against hanging boys before they are proved to be guilty. Thus it is brethren, that the subscription is diminished towards my support.”[10]

Despite the financial difficulties and being fired and rehired from his position as pastor, Obed and Charlotte Dickinson continued to speak out and try to make a difference. The abolition of slavery was not enough. “It is true, we have no slavery now in Oregon, but we have that which is equally wrong: a prejudice and a hatred to the oppressed race…” Obed wrote in 1863 using as examples the barring of black students from the public school in Salem and refusal of Salemites to attend a church that allowed black people to attend the same services and sit in the same seats as white members. [11] Charlotte, a teacher, could do something about educational opportunities. She began offering lessons after hours for black students denied admittance to public school, two hours every evening.[12]

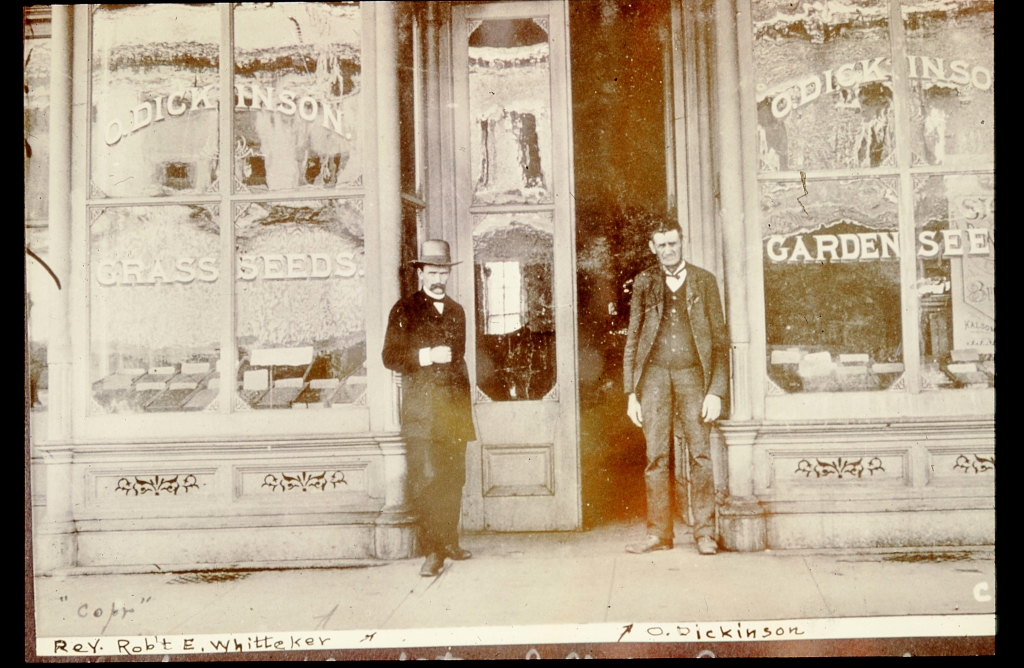

The relationship between pastor and congregation did not improve, and Obed ultimately resigned his position in 1867, this time for good.[13] His sideline seed business, started to help supplement the small salary he was making as pastor, suddenly became the family’s sole line of support.

As we celebrate Independence Day this weekend, and light firecrackers to remember the struggle for “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” I’m going to remember this little scrap of paper. The struggle wasn’t over in Dickinson’s time, nearly a century removed from the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It would take another century for Civil Rights movement to gain more ground. It continues today.

This article was written by Kylie Pine and published in the Statesman Journal 5 July 2020. It is reproduced here for reference purposes, with citations included.

Citations

[1] Biographical details taken from obituary for Obed Dickinson. See “Answered the Summons” Oregon Statesman 29 Nov 1892 pg 4. It is interesting to note that the story of their journey to Oregon is in the plural in Obed Dickinson’s 1892 obituary. “Mr. Dickinson and his wife sailed from New York….for Oregon as home missionaries…They came at once to Salem and immediately took charge of the Congregational church…They found no house of worship…Their first meetings…

See also: “Missionaries for the Pacific” Weekly Oregon Statesman 15 Jan 1853 pg 2, lists Obed Dickinson as passenger of the ship “Trade Wind.”

[2] See church history recounted in “Answered the Summons” Oregon Statesman 29 Nov 1892 pg 4, which states that “Subsequently an old shop was fitted up and located on the site of the present church. Upon this site they subsequently built the present church which was dedicated August 28, 1863.” The 1871 City directory lists the church as located at the SE Corner of Liberty and Center Streets. Salem City Directory, 1871 pg 73. Accessible here: https://www.willametteheritage.org/1871-salem-city-directory/. Part III. It should be noted that in Egbert Oliver’s Obed Dickinson and the War on Sin in Salem his illustration of the church building is captioned on the “southwest corner of Center and Liberty Streets.” The 1884 Sanborn Fire Insurance map for the city (April 1884 – accessed via Proquest’s Digital Sanborn Maps Database) shows a church building (labelled as “church”) on the southeast corner of Liberty and Center Streets, and a dwelling (labelled “Dw’g”) on the southwest corner, seemingly confirming the location.

[3] “Present church which was dedicated August 28, 1863” “Answered the Summons” Oregon Statesman 29 Nov 1892 pg 4.

[4] Quint, A.H. “Statistics of the American Orthodox Congregational Churchs, as Collected in 1859

Published in Congregational Quarterly, January 1860. Report of Oregon Churches Dated August 1, 1859. Accessible via GoogleBooks, pg 133.

[5] IBID

[6] Article XVII from the State Constitution (Second Part) See digitized materials made available via Oregon Historical Society Research Library on page: https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/exclusion_laws/

[7] Read more about exclusion laws in Greg Noaks Oregon Encyclopedia article: https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/exclusion_laws/

[8]Oliver, Egbert. Obed Dickinson’s War Against Sin in Salem 1853-1867. Portland, Or.: The Hapi Press, c.1987. Pg 141-143

[9] Oliver, Egbert. Obed Dickinson’s War Against Sin in Salem 1853-1867. Portland, Or.: The Hapi Press, c.1987. pg.140

[10] Oliver, Egbert S. “Obed Dickinson and the “Negro Question” in Salem.” Oregon Historical Quarterly. Vol 92, No. 1 (Spring 1991) pp 11-15

[11] Quoting Dickinson’s February 3 1863 letter to the Missionary society in Oliver, Egbert S. “Obed Dickinson and the “Negro Question” in Salem.” Oregon Historical Quarterly. Vol 92, No. 1 (Spring 1991) pp 25

[12] Oliver, Egbert S. “Obed Dickinson and the “Negro Question” in Salem.” Oregon Historical Quarterly. Vol 92, No. 1 (Spring 1991) pp 19

[13] ”Answered the Summons” Oregon Statesman 29 Nov 1892 pg 4; ”Gleanings of the Week.” Weekly Corvallis Gazette. 09 Feb 1867 pg 2. “Rev. O. Dickinson has resigned the pastoral charge of the Congregational Church at Salem. He will travel the ensuing season for the benefit of his health. The Church has tendered a unanimous call to Rev. P.S. Knight of Oregon City tot take the pastoral charge.

Transcription of other Primary Documents

Oregonian (newspaper) announcement of Seed Business. Morning Oregonian. 19 Aug 1867 pg 2.

Rev. O. Dickinson, proprietor of the extensive seed gardens northeast of Salem, a short distance, has just returned, says the Record, from a long tour in Oregon and California, to settle accounts with the various persons who have been disposing of his garden seeds. His enterprise is a new one, and we are pleased to learn that he considers the success attained sufficient inducement to prosecute the business more thoroughly. His sale of seeds amount, this year, to nearly $2000, and those who have done business with him in California say they can sell three times the amount another year, judging probably from the success of those who have purchased and planted them the present season.

Leave A Comment