The Interesting Story of the White Sox Orchards

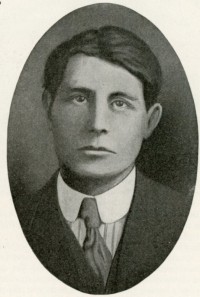

Much to the disappointment of his fans and teammates, Tinker A. Jones gave up money and fame in Chicago to settle in Oregon and invest in fruit farms, timber and wheat in Oregon. Photo Source: May edition of Sunset The Pacific Monthly, 1912. WHC Collections, 2018.001.0029

While thumbing through a May 1912 edition of Sunset magazine[1] in our collections last week – as you do apparently if you work in a museum — I came across the bizarre story of three members of 1906 World Series teams that were lured by siren song of Oregon’s rich agricultural land.

While the game has passed out of living memory, the 1906 World Series was long considered one of the greatest upsets in baseball history. The matchup pitted the Chicago Cubs, that season having won more games in a single season than any team ever, against their cross-town rivals: the Chicago White Sox. The Sox, too, had a reputation. Despite the worst team batting average in the American League (.230) they had clawed their way to the pennant and earned the nickname “Hitless Wonders.” They must have been saving up, for in the last two games of the series they racked up 26 hits and the world championship.[2]

Oregon, where baseball players go to retire?

Just six years later, three players from that contest had made their way west to Oregon, seeking their fortunes not in diamonds (as the magazine puns), but in rich agricultural and timber lands. The first lured to Oregon was the White Sox player/manager Fielder A. Jones. Jones got his professional start playing for Portland in the Oregon State League in 1893.[3] At its inception, the league had four teams representing Albany, Portland, Oregon City and Salem.[4] Jones would go on to play with the (I kid you not, an honest-to-goodness National League Team) Brooklyn Bridegrooms before being picked up by the White Sox in 1901.[5] He played as an outfielder and transitioned in 1904 to the role of player/manager. Apparently, Jones had a threatened to leave the game of baseball early and return to Oregon to join an outlaw league in Portland as early as 1903, but the threat wasn’t made good on until after the 1908 season.[6] Threats and offers of a “greater salary than is now paid to any of President Taft’s cabinet officers” couldn’t convince Jones to return to Chicago and give up the opportunity to “live in peace and comfort with his family.”[7] He invested in Timber and convinced former teammate, catcher Billy Sullivan, to invest in a 526 acre fruit farm in the Chehalam Valley near Newberg which was duly named “White Sox Orchards.”[8] Sullivan was elected president of the company which primarily grew apples. The newspapers throughout the east reported the investment and Sullivan’s enthusiasm in the project. He even tried to convince other teammates and Chicagoans to invest.[9] Both Jones and Sullivan took every opportunity to market the apples from their orchards. When the team made a long stop in Portland on their way to a game in San Francisco, there was a box of White Sox Orchard apples waiting for them at the station along with a greeting by former teammate Jones. As the L.E. Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune reported: “In the crowd at the station was a delegation from the White Sox Orchards company, of which Billy Sullivan is vice president. A big box of great red apples from one of the company’s orchards was put aboard the special train with best wishes for the team’s success. The apples looked so tempting in the packing case that a strict guard had to be kept over the until everyone took a look at the beauties. Then V.P. Sullivan started distributing them, and in half an hour there was nothing left except the box and its decorative label.”[10]

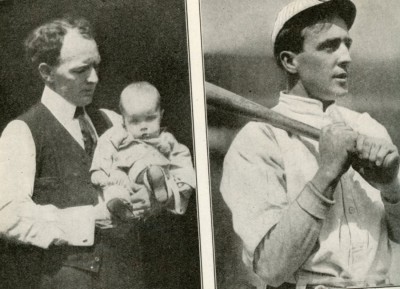

Billy Sullivan (left) and Joe Tinker were two professional baseball players that were enticed to invest in Oregon fruit tracts in the 1910s. Photo Source: May edition of Sunset The Pacific Monthly, 1912. WHC Collections, 2018.001.0029

The third player featured in Sunset was hall of famer Joe Tinker who the magazine describes as “a ball-player by vocation and a horticulturist by instinct.” If the name sounds familiar, it became a byword in Cubs history as the line “Tinker to Evers to Chance” was immortalized in poetry.[11] Tinker, who played professional ball in Portland for a season before joining the Cubs, also owned 45 acres of fruit land in Oregon.[12]

The Sunset article envisioned that the investments made by the ball players would provide for them in retirement. “Amid the spreading branches of the luscious fruit trees these national figures will spend the closing days of their lives until the supreme umpire shall call three strikes and out. Fancy, if you can, a more ideal ending to a successful career in any vocation.” It even suggested that the orchard and the apples it grew might eclipse the fame of the three players and even baseball itself.

That didn’t quite pan out. The Company’s packing plant in Newberg was sold off to the Salem-based Oregon Grower’s Co-operative association in 1922 and the company faded into obscurity, although Sullivan was still invested in the orchards.

Epilogue

Although replete with imagery of retirement, none of the three players was done with baseball in 1912 and ready for life on the farm. After a stint coaching at Oregon Agricultural College (now OSU) to a divisional title, Jones would return to the majors for a few more years and manage the St. Louis Browns. Sullivan would play his last game in 1916 and return to the Newberg area where he would live until his death just short of his 90th birthday. He umpired and coached locally and his two sons played with the Salem Senators, adorably at first and second base. Younger son Billy had quite the career of his own, playing at Notre Dame and professionally with his father’s White Sox and several other teams, where he played against the likes of Babe Ruth. And Joe Tinker, well, he would end his hall of fame career in 1916, retiring to Florida where for many years Tinker Field, the spring training ground for the Senators and the Twins, bore his name.

Article by Kylie Pine. Article appeared in the Statesman Journal Sunday, October 7, 2018. It is reproduced here with citations for reference purposes.

Cited Sources

[1] May edition of Sunset The Pacific Monthly. WHC Collections, 2018.001.0029

[2] “1906 World Series” Wikipedia.org

[3] Phanne, A. “The White Sox Orchards”Sunset. May 1912. Pg 602. States “Fielder A. Jones who made his professional debut in baseball at Portland in 1895 and who now makes his home in Portland.” Baseball reference.com shows his Portland stint in 1893, having played for teams in Binhampton and Springfield in 1895.

[4] “Oregon State League” Capital Journal 12 May 1893 pg 4; “The Oregon State League” Oregon Statesman 12 May 1893, pg 1; “Semi-Professional Baseball” Oregon Statesman 28 Apr 1893, pg 4. The Salem Club was affiliated with Independence for a while, too. See “Baseball” Capital Journal 8 Jul 1893, pg 4.

[6] “Outlaw League Man.” Oregon Daily Journal 29 Oct 1903, pg 5.; “Won’t Play in Their Yard. Capital Journal 29 Oct 1903,m pg1. Report the news of Fielder not wanting to play in the East. However, his stats on Baseball Reference.com show that he played with the White Sox that year.

[7] Phanne, A. “The White Sox Orchards”Sunset. May 1912. Pg 602

[8] “Sullivan a Land Owner” Altoona Tribune 26 Nov 1909 ,pg 11 newspapers.com; “American League Notes” Sporting Life, December 4 1909

[9] Evening Star (Washington DC) 9 Jan 1910 newspapers.com

[10] Sanborn, L.E. “Whitesox begin last lap of trip.” Chicago Tribune 05 Mar 1910 pg 14 via newspapers.com

[11]“Baseball’s Sad Lexicon” Wikipedia.com https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baseball%27s_Sad_Lexicon

[12] Phanne, 603.

Leave A Comment