It started out as an easy question. When was Salem first electrified? In preparing for the museum’s upcoming exhibit – Yesterdayland: Innovations of the Past – it became clear that the introduction of electricity to our homes and places of business completely revolutionized the way we lived and worked. It just takes one power outage to appreciate the extent to which our lives today are electricity-driven. Yet, for such a watershed moment in our community history, it has been challenging to document the integration of electricity into our early community infrastructure.

I have spent a frustrating couple of weeks pouring through newspapers trying to track down particulars. It appears that the first practical application of electricity in our community was for lighting. Although Salem had relied upon gas and oil street lamps since the late 1860s, their dull glow and inconsistent lighting schedule left much to be desired.

First Calls for Electric Lights

The first movement in the Mid-Willamette Valley for the introduction of an electric light system was spurred by the Oregon State Legislature in 1885, passing legislation to light public buildings in Salem.[1] In January 1886, the Portland-based Oregon Electric Light Company (headed by Captain S.W. Blaisdell) officially contracted with the state to provide lights to the State Capitol, insane asylum and penitentiary for ten years in exchange for $5,000 a year, a building at the Oregon State Penitentiary to run their equipment and water rights.[2] In the months that followed the award of the contract there was a flurry of activity documenting the comings and goings of the Oregon Electric Company’s managers and their renowned electrician, “Professor” Nathaniel S. Keith who was helping to design the system.[3] The stringing of wire[4] through the capitol and importation of machinery[5] all became newsworthy events.

Salem City Council Gets on Board

This activity caught the imagination of members of the Salem City Council,[6] and after hearing a presentation from Capt. Blaisdell, approved a motion to contract with the Oregon Electric Light Company to provide “2000-candle power at $12 per month, provided that not less than ten lights be taken.”[7] Ordinance No. 158 followed on June 19, 1886 to give the company not only the right to create and maintain an electric system, but also the right to erect poles and wires within public streets and alleys. The ordinance also criminalized the vandalization of any company property.[8]

As opposed to the state’s system for the capitol and other state agencies located at the penitentiary, the city’s lighting plant was to be located at Thomas Holman’s agricultural works that stood at the southwest corner of Trade and High Streets (today the location of Salem Fire Station No. 1). The site was strategically located along the mill race and already developed to power to the industries clustered around it like Holman’s shop.[9]

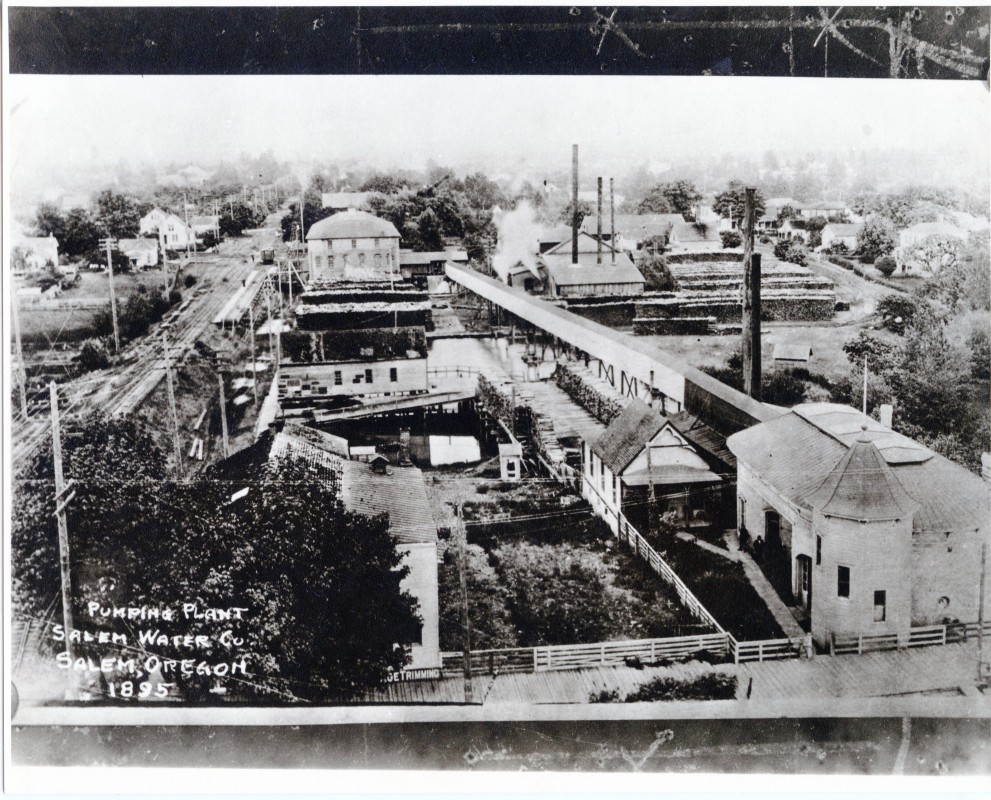

View showing the site of the lighting plant that supplied electricity to Salem’s streetlamps for the first time in 1886 at the corner of Trade (running parallel to the left edge of image) and High Streets (in distance). By the time this photograph was taken in 1895 the site had been altered by fire and changes to the system, including the installation of a brand new, steam-powered Corliss engine where the three stacks for the boilers can be seen in the back right of image. Photo Source: Willamette Heritage Center, 2015.025.0005

Both plants used dynamos to convert mechanical power from a water-powered turbine into an electrical current. [10] Additionally, the city plant was fitted up with a steam boiler that could be used as a backup to the waterpower or to supplement the power needs of the plant.[11]

Community Comes Out to See New Technology

By the Summer of 1886, all of Salem was abuzz to see the new electric light systems in place. When the state’s system was rumored to be tested on the capitol grounds one July night, the Oregon Statesman newspaper sent out a full contingent to document the spectacle. As rival paper the Willamette Farmer humorously reported: “…with its usual enterprise, [the Statesman] had eight men and nine boys stationed in the vicinity of the State House, watching for any manifestations of electricity, or any other unusual demonstrations on the part of the poles, nothing happened. Three men and two boys solemnly averred that the light on the northeast corner was started up, but after thorough investigation the local editor gives it as his deliberate opinion that it was the planet Jupiter that they saw.”[12]

Lights Get Turned On

July 31, 1886 the wait was over as the Holman plant[13] and city street lights made their first public test. The paper declared it a success. After all the hoopla earlier in the month, a very sedate description was given: “The lights burned very brilliantly, and appeared to burn very evenly, and with but little flickering…At half-past 11 o’clock they were doing much better work than earlier in the evening. Salem can congratulate herself.”[14] The state’s system was a little slower to get up and running. Tests of the system started as early as September 6th[15], but regular service to the capitol and penitentiary would not be established until October 1.[16]

Effects of New Lights

Not everybody was wild about the new system. One editorial claimed that the new lights were a “most harmful and pernicious invention” that would put lamplighters out of work, extend the day to 24 hours preventing anybody from sleeping, “destroy the usefulness of the stars and the moon,” and generally turn everything “topsy-turvy.”[17]

In the few days following the first test, there were several reports of birds and other wildlife suffering ill effects attributed to the new lights. After finding an owl dead under a light pole, one reporter hypothesized that “the light blinded the owl, and it flew against the wires with such force as to kill it.”[18] One enterprising entrepreneur took advantage of the lights’ effect on insects to boost his pesticide sales. “The electric lights are death to insects, but they don’t kill half as many as Port’s insect powder.”[19]

The new lighting system was also blamed for strange phenomena, from interference with telephone lines[20] to occasions of smoke issuing from the roots of trees. In the later, Mr. Rhodes, a janitor at the Marion County Courthouse, having observed what he thought was smoke from a discarded cigar under a tree on the courthouse lawn went to investigate, and upon touching the tree received an electric shock. Still concerned about the smoke, he went and got a bucket of water to put out the slightly sulphuric smelling smoke coming from the tree’s roots to no effect. The reporter had no explanation for the phenomena, except that it might have something to do with the new lights.[21]

Generally, though, it seems the community embraced the new lighting system. In an article entitled “Salem’s Boom,” T.T. Geer reflected on the change: “A good portion of the city has recently discarded the old oil lamps, and substituted electric lights. During the past week these have been extended to the state prison in the eastern suburbs, which seem like sending a gleam of hopeful gladness into the darkest recesses of hades. From a hill near my house, nine miles distant, these lights can be plainly seen on a clear dark night.”[22]

First Lights, then…

It would be a few more years before electricity would make its way toward powering a streetcar system in Salem[23] and many more before electricity made its way into the homes of ordinary folk, but the revolution had begun.

This article was written by Kylie Pine. It first appeared in the Statesman Journal in June 2018. It is reproduced here with citations and additional information for reference purposes.

Citations

[1] The Morning Astorian 13 Jan 1886, pg 3, references an act approved Nov. 30 1885. The Special Session has text related to the bill, and also refers to an act of the regular February session of 1885. Could not locate legislation within the record.

[2] Technically, the legislation was passed in November of 1885. (Morning Astorian. 13 Jan 1886 pg 3). The contract does not appear to have been signed until January 1886. “Those Electric Lights” Oregon Statesman. 6 Jan 1886, pg 3. See also. “Contract Made.” Oregon Statesman. 12 Jan 1886 pg 3.

[3] “The Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 18 Feb 1886 pg 3. “Electric Light.” Oregon Statesman. 11 Marh 1886, pg 4. “Electric Lights. Weekly Oregon Statesman. 23 Apr 1886, pg 6.

[4] “Laying of the Wires Progressing.” Oregon Statesman. 18 Mach 1886, pg 3. “Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 26 March 1886, pg 3.

[5] “Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 9 May 1886, pg 3. “The Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 18 May 1886, pg 3. “The Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 22 May 1886.

[6] “Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 13 April 1886 pg 3. Councilor John Hughes visits Astoria to see lights. Paper surmises that the council might consider plan to electrify. “Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 26 Mar 1886, pg 3. “The city fathers are considering the electric light question now themselves, but they will probably not take any action in the matter of lighting the city until after they see the quality of the lights now being erected.”

[7] “City Council.” Weekly Oregon Statesman. 16 April 1886 pg 8.

[8] “Ordinance No. 158.” Oregon Statesman. 22 June 1886 pg. 2. Approval date of June 19, 1886, signed by W.W. Skinner, Mayor.

[9] “The Electric Lights” Oregon Statesman. 16 Jun 1886 pg 3.

[10] “The Electric Lights” Oregon Statesman. 16 Jun 1886 pg 3.

[11] “Those Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman. 3 Jul 1886 pg. 3. Note that this article mentions the arrival of “the boiler for the city electric light plant on Thursday, and yesterday it was placed in position at the agricultural works.” The rationale behind its status as a backup system comes from an article “Be Ready by Friday” Oregon Statesman 25 Aug 1886, pg 3 which states that “they are now running by a temporary engine.” XXXXXXX.

[12] “The Electric Lights.” Willamette Farmer. 09 July 1886 pg 5

[13] The plant at the corner of High And Trade is often referred to as Holman’s plant. In part because of its location at Holman’s agricultural works, but also because Holman purchased the plant from the Oregon Electric Light Company in July of 1886. See “Electric-light plant sold.” Oregon Statesman. 10 Jul 1886, pg 3. It is unclear from this article whether Holman purchased all of the Oregon Electric Light Company interests (including the power plant at the penitentiary, or just the Holman site plant). Blaisdell and the company continue to be mentioned in later newspaper articles as principal parties to the Oregon Electric Light Company and being in Salem. (see Oregon Statesma 28 Sept 1886, pg 3. Oregon Statesman 3 Oct 1886,. Pg 2. However, several years down the line, Holman writes as president of the Oregon Electric Light Company to the Legislature to extend the contract it first made with Blaisdell, et al. See: “The Electric Lights.” Capital Journal 13 June 1888 pg 3

Thomas Holman, the proprietor of the Oregon Electric Light works, sent the two arc dynamos to San Francisco to-day to be repaired by N.S. Keith, the inventor. Mr. Holman expects to have the lights burning again before long.

Mr. Holman is now clearing away the debris in the west end of the burned building, in order to make a place for the dynamos on their return.

“City Council” Capital Journal 15, June 1888 pg 1

Expenses: Salem Electric Light Co. 214.50

Journal of the house of the Legislative Assembly fo the State of Oregon, volume 15 page 199.

Friday, February 1, 1889.

Morning Session

…

Communication

To the Legislative Assembly of the State of Oregon:

Whereas, at a special session of the legislative assembly in the year 1885, an Act was passed authorizing the State to enter into a contract with the Oregon Electric Light company for the term of ten years.

Said contract was entered into by the proper State officers as required by said Act of the Legislative Assembly in which the said Oregon Electric Light Company agreed to light the State penitentiary buildings and the State capitol for the said term of ten years for the sum of $5,000 per annum, of which two years have already expired, leaving eight years yet for the contract to run.

Lights are now needed at the State insane asylum, that building having already been wired ready for use.

The number of lights required to be furnished by the Oregon Electric Light Company having been furnished, the said company are not required to furnish the light required at the asylum.

The machinery at the penitentiary which drives the electric light plant belongs to the State.

The plant of the electric light company cost about $17,000. The company now pay for operating the same $125 per month, leaving a profit of say $3.500 per year. They now offer to sell the plant, together with the contract for eight years to run, to the State, and will take for the same $23,000, or will sell the plant, together with the unexpired termo f eight years, less $1,500 per year for expenses and 5 per cent interest compounded on said sum. THE OREGON ELECTRIC LIGHT COMPANY. By Thomas Holman, President. Salem, Oregon February1, 1889

[14] “The First Lights” and “A Success” Oregon Statesman 1 Aug 1886, pg 3

[15] “The Electric Lights.” Oregon Statesman, 7 Sept 1886, pg 3.

[16] “State Service to Begin.” Oregon Statesman. 2 Oct 1886 pg 3

[17] “A Protest.” Oregon Statesman 13 Jul 1886, pg 3.

[18] “Killed by the Concussion.” Oregon Statesman. 3 Aug 1886 pg 3. See also “Birds Caged.” Oregon Statesman 4 Aug 1886, pg 3.

[19] “The Lights.” Oregon Statesman 7 Aug 1886, pg 3.

[20] “Won’t Work.” Oregon Statesman 28 Dec 1886, pg 3.

[21] “A Question for Scientists.” Oregon Statesman 15 Oct 1886, pg 3.

[22] Geer, T.T. “Salem’s Boom.” Oregon Statesman. 6 Oct 1886, pg 2.

[23] 1890.

Leave A Comment