By Kylie Pine (Originally published in the Statesman Journal March 2016)

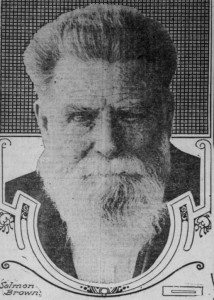

Salmon Brown as he looked when he lived in Oregon. Originally published with an article he wrote in the Oregonian February 25, 1917. Source: Oregon Digital Newspaper Project.

Unless you live off the grid, it has been difficult to avoid the barrage of news coverage of the armed occupation of the Federal Malheur Wildlife Refuge recently. It was amidst this constant chatter that I ran across an interesting local connection to our country’s most famous armed federal occupier, John Brown.

While their purposes and objectives were utterly different, Brown and the armed refuge occupiers did employ means that struck me as bearing some similarities. Like the militant group occupying the wildlife refuge, John Brown’s plan was to forcibly take over federal property. Brown, an ardent abolitionist, had spent time escorting African-Americans through Ohio to freedom in Canada on the Underground Railroad, and more time fighting battles against pro-slavery settlers in the free state of Kansas. Not satisfied, he hatched a plan to take over the armory at Harpers Ferry and start an armed slave rebellion in 1859. The raid ended in the deaths of two of Brown’s sons and the eventual trial, treason charge, and hanging of John Brown himself. Nevertheless, John Brown became a martyr for those espousing the anti-slavery cause and his fame lives on today, even in our modern popular culture. Anyone remember the camp song about John Brown? Set to the old camp meeting song that would eventually become the tune for the Battle Hymn of the Republic, the original lyrics had John Brown’s body lying “a-moldering in the grave.” Our edited version as kids usually had to do with his baby having a “cold upon his chest.” Come to find out that his baby (at least one of 10 children) had spent significant time right here in Salem.

Salem Connection

The first hint of this connection came from a small article in the 1980 Marion County Historical Society newsletter: “John Brown of Harper’s Ferry fame…had a son, Salmon, who wound up in Salem about 30 years after John was hanged for his 1859 assault on the U.S. arsenal. Oldtimers say Salmon came from California, first lived on N. Front St. near Marion Square, then to 1243 Marion St., near the present Olinger Pool, owned a meat market at 13th and Center, moved to Portland in the late 1890s.”

When something begins “oldtimers say…” it never hurts to be a little cautious about trusting the source. So I set to work to find a few more documentable facts. When he failed to appear in Salem in the usual places – Census Records and City Directories – I started to get nervous. Luckily, Brown was a bit of a celebrity and newspaper records contain countless articles by him and about him that start to give view to his experience.

Salmon Brown was born Ohio in 1836. His father, at the time of his birth, was raising sheep and working as a tanner.

[1] He followed in his father’s footsteps to Kansas and was actively involved in the fighting between pro and anti-slavery forces prior to the Civil War. While he claims to have participated in the Battle of Black Jack, an attempt to rescue two of his brothers, he was not present for his father’s attempt to take over Harper’s Ferry. As his wife claimed in an interview, “One of the boys had to stay at home. That lot fell to Salmon.”[2] His father’s involvement in the affair would affect the course of the rest of his life. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted and was set up to become an officer in the New York 96th Infantry, but never saw action on the battlefield. Accounts through multiple newspapers vary, but the most interesting one states that fellow officers petitioned that he be removed from their ranks, citing the fear that when the other side discovered Brown’s ancestry, his unit would be put in greater danger as they looked for revenge against the martyr of Harper’s Ferry.[3]

So Brown went West, arriving in California in about 1864 where he engaged in his father’s original trade of sheep raising until the winter of 1893 killed a large portion of their flock.[4] The family then headed north intending to settle in Seattle, but ended up settling in Salem after seeing the community. Although I could find no evidence of an actual address, one newspaper reports that the family settled in the Englewood neighborhood and confirms that he did run a meat market.[5]

Purportedly Salmon Brown’s House. Photo found in Al Jones Collection has inscription: “John Brown’s Son’s Home. Looking north from East School.” No citation information was provided in inscription. If this is the case it would have been located just north of the intersection of Center and 12th Streets in Salem. Photo source: Al Jones Collection, WHC 2004.010.0578.

By all accounts, he very much resembled his famous father. One reporter lyrically wrote: “Looking closely at the portrait of John Brown and then again at his son, one can see a strong resemblance, which Mrs. Brown says is growing as her husband becomes older. The same determined look is set on the face, while in the wearing of his hair and the trimming of his mustache, the son has followed his father closely.”[6] His connection to John Brown was continually exploited on the political scene, Salmon’s opinion making its way into op-ed pieces and his appearances at debates frequently reported.

Salmon and his wife moved to Portland in about 1901.[7] He had suffered the physical effects of a horse accident for nearly 35 years and towards the end of his life spent much of his time in bed. He died in Portland from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1919.[8]

Family Connections

Nellie Brown (right) and Lottie French (left). Al Jones Collection, Willamette Heritage Center 2007.001.1273

This image was found in the Willamette Heritage Center Collections with the inscription on paper paperclipped to the back of image read: “R – Nellie Brown, daughter of Salmon Brown July 14, 1894 L-Lottie French.” It unfortunately gives no details as to where the image came from. By searching for Nellie we were able to piece together a few more pieces in the Brown family story.

They show up as a family in the 1880 US Census living in Yager Creek, Humbolt County, California: Salmon, head, Abbie wife and seven children: Minnie, Inez, John, Edward, Ethel, Agnes and Ellen. I suspect Ellen was soon to be nicknamed “Nellie.”

By 1900, the family is listed in the US Census as living at 417 Marion Street, an address that would nicely fit with the description of the house given in the picture above. Salmon is listed as head of household, with wife Abbie, son Edward (a thirty year old stockbuyer), daughter Nellie (21, a music teacher), and granddaughters Muriel and Edna Scott (ages 16 and 14 respectively). Given the different last name and the birth places listed for their parents, this is assumed to be the daughters of one of Salmon and Abbie’s daughters.

Now the story diverges. There is a Washington marriage record for a Nellie Brown marrying an Edward J. Groves and 2 September 1902 in King County, Washington. The reason I think this might be our Nellie Brown, is because in the 1910 US Federal Census this couple shows up living in Portland and Nellie B. Groves is working as a music teacher, the same as listed in the 1900 Census. Could just be coincidence, but it is kind of compelling, too.

Citations

[1] “John Brown’s Son in Portland: Reminiscences Regarding the Central Figure at Harper’s Ferry in Days Before the War.” The Daily Capital Journal. April 20, 1901, pg 5

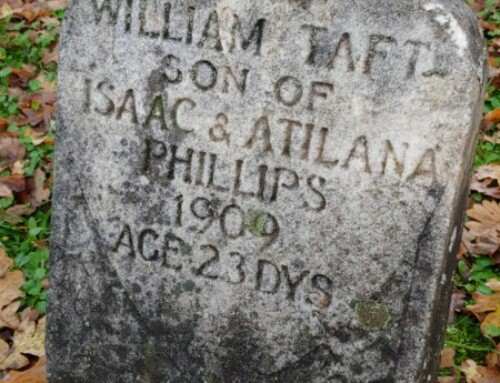

Gravestone –Referenced through Find-a-grave.com

[2] John Brown’s son is Mentally Keen at 80 Oregonian July 5, 1906, pg 5

[3] “John Brown’s Son in Portland: Reminiscences Regarding the Central Figure at Harper’s Ferry in Days Before the War.” The Daily Capital Journal. April 20, 1901, pg 5 States that he moved there a few weeks ago – meaning 1901.

John Brown’s son is Mentally Keen at 80 Oregonian July 5, 1906, pg 5. This article intimates that he moved to Portland in 1902.

[4] “John Brown’s Son in Portland: Reminiscences Regarding the Central Figure at Harper’s Ferry in Days Before the War.” The Daily Capital Journal. April 20, 1901, pg 5;

John Brown’s son is Mentally Keen at 80 Oregonian July 5, 1906, pg 5

[5] States Rights Democrat, Sept 29, 1893, pg 2

“Mistook the Man” Capital Journal February 12, 1898, pg 2

[6] “John Brown’s Son in Portland: Reminiscences Regarding the Central Figure at Harper’s Ferry in Days Before the War.” The Daily Capital Journal. April 20, 1901, pg 5

[7] “John Brown’s Son in Portland: Reminiscences Regarding the Central Figure at Harper’s Ferry in Days Before the War.” The Daily Capital Journal. April 20, 1901, pg 5

[8] Salmon Brown Victim of Self-Inflicted Wound. Daily Capital Journal. May 12, 1919 pg 3

Leave A Comment