Why is the city of Salem Oregon’s Capital?

By Kylie Pine

Why is Salem Oregon’s Capital? I was asked this question twice this week and took it as a sign. As with most simple questions, this one is not that easy to answer. The question is understandable. Portland, even without its numerous suburbs, has long out-populated Salem.[1] To many fifth graders taking geography tests and out of town visitors Portland seems like a more likely candidate for the capital. So how did Salem get the honor? The short answer is: it’s complicated. The selection of Salem as the seat of Oregon government came only after years of bickering and fighting that makes some of our most recent political squabbles look downright pleasant by comparison.

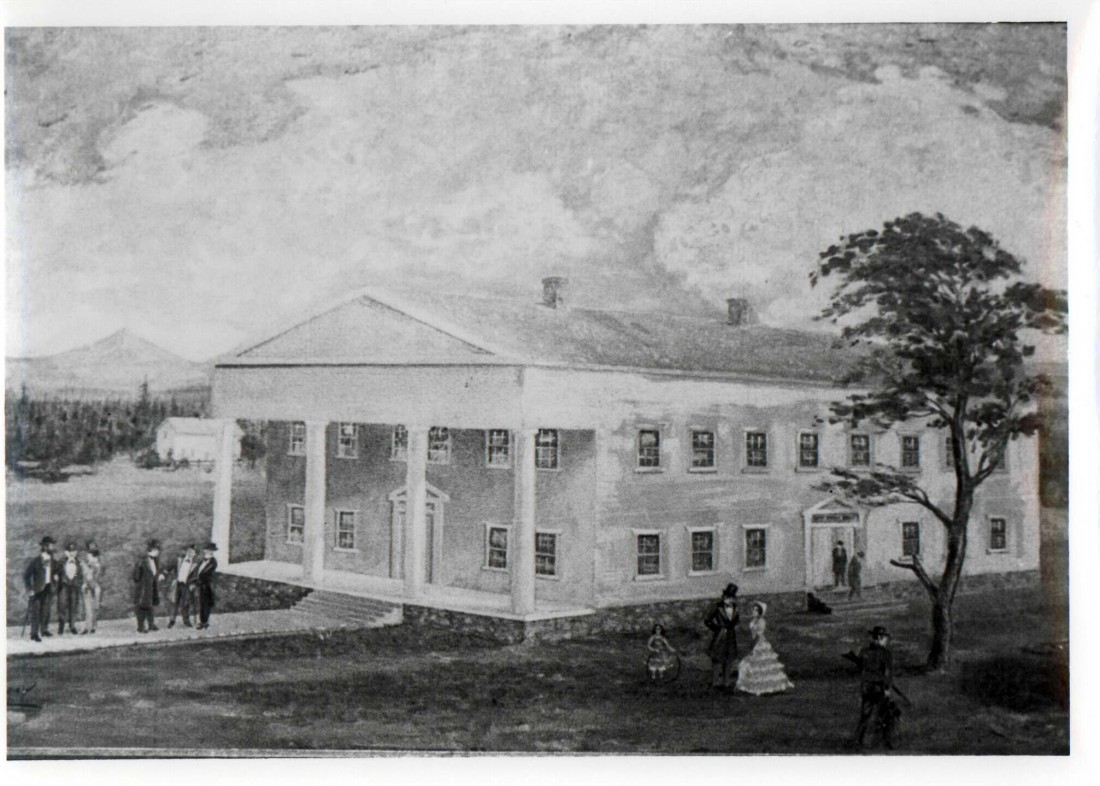

Thanks to the infrastructure of the Methodist Missionaries who set up their headquarters here in 1841, Salem (or Chemeketa as it was then known) was one of the earliest and fanciest Euro-American settlements in the Oregon Country. The stately Lee House, Parsonage and School buildings provided some of the largest gathering spaces around. They became one of the meeting places for the early Euro-American settlers as they worked their way towards a provisional government parsing through legal issues such as wolves attacking livestock and rich moonshiners dying without wills. You have to remember that up through 1846, the Oregon Country was jointly claimed by Great Britain and the United States and jurisdictional issues abounded. [2] The solution was to create an independent government, which happed via a vote at Champoeg in 1843.

After the founding of the provisional government, a good chunk of the governing and meetings shifted to Oregon City[3], where a lot of the legislative sessions were held in private homes and in the Methodist mission building and church.[4] Oregon City had the advantage of being more centrally located, at least for the elected officers.[5]

Despite Oregon City’s charms, the territorial legislature passed a bill titled: “An Act to provide for the selection of places for the location and erection of public buildings of the territory of Oregon,” on February 1, 1851. In the bill named Salem was the territorial capital, Portland as the site of the territorial penitentiary and Marysville (now known as Corvallis) as the site for the territorial university. [6] It appeared pretty clear. Law passed, Salem is the capital, right? Except that being the seat of the government brings a lot of jobs and revenue to the surrounding community. Legislators and lobbyists need to eat, sleep, board their horses and, in the case of many early Oregon legislators, drink (a lot). Many communities realized the economic gains that could come from being the capital city. Cue the next decade of political infighting!

The first attack on Salem’s capital-hood, came from then Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines right after the 1851 bill was passed. After giving a speech against the act to the legislative assembly, he wrote to the U.S. Attorney General apparently just to make sure the act was legal.[7] The Attorney General J.J. Crittenden, with approval from the office of the President, wrote back and basically said not so fast. While I agree, that the U.S. Congress gave you full powers to choose wherever you want your seat of government to be, you didn’t exactly follow the rules in naming your act, so it should be considered null and void.[8] Editorials fly, legislators refuse to meet in Salem,[9] and people hold random meetings voting to disregard laws passed at Salem.[10] Much of the contention seems to fall along party lines, the Whigs in opposition to Salem and the Democrats for it.[11] Oregon’s three person Supreme Court split along party lines, offering two opinions against Salem to one for it.[12] Salem seems to be on the losing side until Oregon’s Democratic Senator, Joseph Lane, weighed into the fray by proposing a joint resolution in the U.S. Congress to confirm Salem as the capital and to confirm the “lawfulness of the proceeding of the Assembly at their late session at Salem.”[13] The resolution unanimously passes, but controversy did not end.

Not even the construction of a capitol building in Salem could stop the controversy. Before the building can even be completed the legislature votes to move the capital to Corvallis, [14] [15] but the move is short lived. The legislature soon makes plans to return to their building in Salem. Unfortunately for the legislature (and for Salem) the building catches fire. [16] Even though arson was never proved,[17] some claimed that capitol was intentionally burned by folks who did not want the government located in Salem.[18]

From then on other capital options are pretty consistently raised in the press and in the legislature. Eugene and Portland are all seriously considered alternatives.[19] Another bill is introduced to decide the question once and for all, which proscribes the issue be decided at a general election.[20] An election is held, cheating is accused,[21] and another election is proposed.[22] Still a contentious issue, Oregon’s constitution framers in 1857 gave the responsibility of choosing a “permanent seat of government” to the voters, requiring that whatever was decided could not be changed for 20 years, and (probably wisely given the history of the conflict so far) refused to appropriate money for a statehouse prior to the year 1865.[23]

So what do legislators do? Introduce several more bills to decide upon a capital, which some would argue were contrary to the constitutional provisions.[24] Finally, general elections were held in 1862 and 1864. Salem beat the next closest vote getter (Portland) by twice as many votes in both elections.[25]

Perhaps the election was the decisive proof the state needed that the capital belonged in Salem, or perhaps, as one editorial writer suggested “people [were] heartily tired of the tiresome question.”[26] Whatever the case, Salem remains the seat of government.

This article appeared in the Statesman Journal on Sunday, November 6, 2016. It is reproduced here with citations and additional contextual information for reference purposes. The author would like to express appreciation for the staff at the Oregon State Archives for their help uncovering some of the documentation of this period of time.

Transcriptions of Selected Documents

There is enough research potential in this topic to fill volumes, let alone an 800 word article. The following are documents I transcribed in the research process that may be of some reference use. They are reproduced as I transcribed them and may not represent the entire document or source. I have provided an annotated paragraph preceding each with information about where I found the source and context. They have been arranged in chronological order.

Opposition of Governor Gibbs to Election Protocols, 1862

This is the veto explanation given by Governor Gibbs to the legislature related to amendments the legislature had proposed to the voting rules for the general election to select a seat of government. It is available through the Oregon State Archives and is printed in: Printed in: Proceedings of the House of the Legislative Assembly of Oregon for the third Regular Session, 1864. Portland, Oregon: Henry L. Pittock, State Printer, 1864.

12: Journal of the Senate:

EXECUTIVE OFFICE: October 22, 1862

Gentleman of the Senate:

On the last day of the last session of the legislature, I received a large number of bills, signed by the president of the senate and speaker of the house, too large a number to property consider before the final adjournment.

Among them was senate bill No. 37 “A bill to amend an act providing for the submission to the electors of this state, the matter of the selection of a place for the permanent location of the seat of government.”

I cannot approve the bill without violating the constitution of this state, as I understand it. I therefore return it to the secretary of the senate, with my objections to be submitted by him to your honorable body.

1st. Sect 22, Art. 4th of the constitution of this state, says: “No act shall ever be revised or amended by mere reference to its title, but the act revised or section amended shall be set forth and published at full length”. The bill under consideration “sets forth, “the section as amended at full length. It also “sets forth,” and publishes the old section, or section amended at full length, contrary to what I consider was the intention of the framers of the constitution. They evidently intended that sections amended should be complete in themselves, so that a casual observer could tell what the law is without finding a part in one section, in one book or place and part in another; but I cannot conceive that they intended the section repealed and amended by the substitution of another section should also be published with the new section. That construction would mislead and greatly encumber the statues with worse than useless matter…

2nd. Again, this bill provides if no place receives a majority of all the votes cast for the seat of government, at the next general election, that is the next general election following, if the two places having the highest number of votes only shall be voted for. Under the constitution, the legislature has no right to say that only two places shall be voted for, any more than that only one shall be voted fort. At the time of the adoption of the constitution of this state, Salem was the capital and it could not be moved there from in any other manner than as prescribed in the constitution.

Sec. 1 Art. 14th of the constitution provides that the legislative assembly shall not have power to establish a permanent seat of government for the state. But at the first regular session after the adoption of this constitution, the legislative assembly shall provide by law for the submission to the electors of this state, at the next general election thereafter, the matter of the selection of the place for a permanent seat of government; and no place shall ever be the seat of government under such law, which shall not receive a majority of all the votes cast on the matter of such selection.

Sec. 3 provides that the seat of government, when established, as provided in section one shall not be removed for the term of twenty years from the time of such establishment, nor in any other manner than as provided in the first section of this article.

Passing the question as to whether or not the capital is established at Salem for twenty years, and upon the supposition that it is yet to be established it clearly follows, in the language of the constitution, it cannot be established in any other manner than as provided in the first section of this article.

What then is the manner provided in the first section? Does it say that any limited number of places may or shall be submitted? Certainly not, but the matter was freely and unqualifiedly “submitted to the electors of the state.”

14: Journal of the Senate:

Any place and all places might have been voted for, then, under the constitution, and the place having a majority over all, would have been the capital.

The members of the first legislative assembly so understood the constitution and passed a law providing for the submission for all places, at each general election until some place should receive a majority of all the votes cast.

Again, if the legislature can limit the number of places, it may name any two places; say Mt. Hood, a prominent point, and Salem as the other. Practically that would be submitting but one place and Salem would be selected. It follows then that the legislative assembly has no power to limit the number of places to be voted for. As well might the legislature pass a law that but one man in the state or county should be voted for, for a representative in congress or in the legislature. The principal is the same in one case as in the other.

As the law now stands, any place and all places may be voted for, and in my opinion, the clause in the bill limiting the places to be voted for, to these having the highest number of votes, is unconstitutional and void.

Therefore I cannot approve the bill.

ADDISON C.GIBBS, Governor of Oregon.

On motion of Mr. Cornelius,

The senate proceeded to reconsider the vote by which the bill was passed.

The bill was then read by its title, and, On motion of Mr. Cornelius, Was put upon the final passage and was lost by the following vote: [2-16] On motion of Mr. Cornelius, the following committee were appointed to draft rules for the permanent government of the senate, viz: Cornelius, Hovey and Hinsdale.

Senate Adjourned.

An Act. To Provide for the Selection of Places for Location and Erection of Public Buildings in the Territory of Oregon, 1851.

This is a partial transcription of the text of this act as it was reprinted in the Oregon Statesman on April 4, 1851, under the title “An Act.” It should be noted that at this point in time the Territorial Legislature had two chambers – the House of Representatives and the Council (not the senate).

An Act.

To provide for the selection of places for location and erection of public buildings in the Territory of Oregon.

Section 1. Be it enacted by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Oregon, That the seat of government of this Territory be, and hereby is established and located at Salem, in the county of Marion, and each and every session, either general or special, of the Legislative Assembly of this Territory hereafter convened, shall be held at the said place above named…

Sec. 3. That the University shall be and hereby is located and established at Marysville, in the country of Benton, and all appropriations or donations of money or personal property, and all the proceeds of the sale of land, granted or donated to this Territory, for the establishment and endowment of a University, shall be applied to the erection of suitable buildings for, and endowment of a University at the said place above mentioned.

Sec. 4. That John Force, H.M. Waller, and R.C. Geer, be, and are hereby constituted a board of commissioners to superintend the erection of buildings at the place designated in the first section of this act as the seat of government, and the said commissioners, or a majority or [sic] them, shall agree upon a plan of said buildings, and shall issue proposals, giving two months’ notice thereof, and contract for the erection of said buildings without delay: and the said commissioners shall agree upon one of their number to be acting commissioner, shall give bond to the United States in the sum of twenty thousand dollars, to be approved by the Governor of this Territory, for the faithful performance of his duty; and said bond shall be filed in the office of the Secretary of this Territory.

Sec. 5. It shall be the duty of said acting commissioner to superintend in person the rearing and finishing of said buildings, and the said acting commissioner shall have power to call the said board of commissioners together, for the purpose of transacting business on this subject; and the said commissioners shall receive such compensation as shall be hereafter allowed by law.

Sec. 6. The acting commissioner shall annually report to the Legislative Assembly, a true account of all moneys received and paid out by him.

Sec. 7. If by death, resignation or any other cause, there shall be a vacancy in said board of commissioners, it shall be the duty of the Governor to appoint some person from the district where such vacancy occurred, to perform the duties of such disqualified commissioner: Provided, however, That such appointment shall not extend beyond the meeting of the next Legislative Assembly.

Sec. 8. And be it further enacted, That a Penitentiary of sufficient capacity to receive, secure, and employ one hundred convicts, to be confined in separate cells at night, shall be erected at the place designated in the second section of this act, for the confinement and employment of persons sentenced to imprisonment and hard labor in the Penitentiary of this Territory.

Sec. 9. That Daniel H. Lownsdale, Hugh D. O’Bryant, and Lucius B. Hastings be, and are hereby constituted a board of commissioners to superintend the erection of a Penitentiary at the place designated in the second section of this act, and shall be governed by, and have all the powers and be subject to all the restrictions contained in sections four, five, six and seven of this act, and receive such compensation as may hereafter be allowed by law.

Sec. 10. This act to take effect and be in force from and after its passage.

Passed the House of Representatives January 38th, 1851 [sic].

Passed the Council Feb. 1, 1851

RALPH WILCOX, speaker H.R.

W. BUCK, President of Council.

Republished Correspondence and Editorial about Location Question, 1851

The following letters between Oregon Governor Gains, U.S. Attorney General John J. Crittenden, State Department Officer Daniel Webster were republished in the Oregon Statesman on August 5, 1851 along with a rather lengthy editorial about the entire issue. They are interesting not only to read for content of legal arguments, but also for their interesting literary style.

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT.

Oregon City, Feb. 6, 1851.

Sir– I have the honor to enclose you a copy of an act of the Legislative assembly of this Territory, entitled “An act to provide for the selection of places for location and erection of Public Buildings of the Territory of Oregon,” passed by that body the 1st inst., and my message of the 3d in relation thereto, and ask the favor of you, and your earliest convenience, to furnish me with an official opinion, as to the validity of the Act in question: and especially whether the Legislative Assembly, can lawfully assemble at Salem, at its next session. Much difference of opinion exists amongst the members, and I am extremely anxious to have the question settled as early as possible.

Very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

JOHN P. GAINS,

Governor of Oregon.

To the Hon. John J. Crittenden, Att’y Gen. Of the U.S. Washington City.

–

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington, May 1, 1851.

Sir I have the honor to transmit to your Excellency, herewith, a copy of the opinion of the Attorney General of the U. States, bearing date the 23d in, touching the several points mentioned in the letter which you addressed to him on the 6th February last: and to inform your Excellency by direction of the President of the United States, that he fully concurs in the official opinion of Mr. Crittenden.

I am, with great respect, Your Excellency’s ob’t serv’t

DANIEL WEBSTER

His Excellency John P. Gaines, Governor of Oregon.

–

OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL,

April 23, 1851.

To the President:

Sir- The papers lately received from the Hon. John P. Gaines, which I communicated to you and which you were pleased to refer to me for my opinion thereon, have been carefully examined and considered. They consist 1st – of what purports to be an Act of the Legislative Assembly of the territory of Oregon – 2nd , a message from Governor Gaines to that Assembly, bearing date 3d of February, 1851, expressing, of reasons given, his dissent to the Act, and his refusal to participate in its execution – and 3dly, an opinion of the United States Attorney for that Territory, given on the application of the Governor against the validity of the said Act.

The only acts of Congress which I have found relating to the subject are, “An Act to establish a Territorial Government in Oregon,” passed 14th August, 1848, and “An Act to make further appropriations for public buildings in Minnesota and Oregon,” passed June 11, 1850.

By the first of these acts, the Legislative power and authority are vested in the Legislative Assembly of the Territory, consisting of a Council and House of Representatives, and the concurrence to [sic] approval, of the Governor is not requisite to the validity of their acts of Legislation. The power “to locate and establish a seat of Government for said Territory at such places as they may deem eligible,” is expressly given to that Assembly by the 15th section of that act.

It may be a question how far this general and exclusive power of Legislation has been qualified by the Act of Congress above mentioned, of the 11th of June, 1850, in the instances therein embraced. That act in its first section, provides “ that the sum of twenty thousand dollars each, be, and the same is hereby, appropriated, out of any money in the treasury not otherwise appropriated, to be applied by the Governors and Legislative Assemblies of the Territories of Minnesota and Oregon, at such place as they may select in said Territories for the erections of Penitentiaries” and in its 3d section it further provides, “ that the sum of twenty thousand dollars, &c, be and the same is hereby appropriated, &c. to be applied by the Governor and Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Oregon, to the erection of suitable public buildings at the seat of Government of said Territory.”

This last section does not in my opinion conflict or interfere with the previous exclusive power of the Assembly to “locate” their seat of Government as they though proper. It gives the Governor no control or voice on that question. But the seat of Government once fixed by the Assembly, it does give him a concurrent and equal authority with them, in the application of the money to the purpose designated. This concurrence was required, probably, as an additional security for the proper expenditure and use of the money granted. And to this extend, and in reference to the use of this money, the Legislative power of the Assembly is qualified, and they cannot dispose of it without the concurrence of the Governor.

In regard to the first section of the act and the appropriation of the twenty thousand dollars for the erection of penitentiary in Oregon, the act is too explicit to leave any room for construction. That money, in the words of the law, is to be applied “by the Governor or Legislative Assembly of Oregon at such place as they may select for the erection of” a Penitentiary. By the force of this language, the Governor must have concurrent and equal power with the Assembly, not only in the application of the money to the erection of the necessary buildings, but in the selection of the place where they are to be erected.

On the other topics presented in the message of Governor Gaines, and in the written opinion of the United States Attorney, it is unnecessary, perhaps, for me to say more, than that I entirely concur in the views expressed by those gentlemen.

The act of Congress, which established the Territorial Government of Oregon, and from which its Legislative Assembly derives its existence and its power, expressly and imperatively declares that, “ to avoid improper influences which may result from intermixing in one and the same “ Act, such things as have no proper relation to each other, very lax shall embrace but one object and that shall be expressed in the title.”

That the act of the Legislative Assembly, in question, does “embrace more than one object,” and that it is, therefore, in violation of the Act of Congress, is a proposition that cannot be made plainer by argument. The sum: “Act of Congress declares what shall be the consequence of such a violation of this xxx, that the Territorial Act “shall be strictly null and void.”

My opinion, therefore, of the Act in question is that it be null and void in all parts, and …validity to anything done under color of its authority.

This statement, with the message of the Governor, the Act of the Legislative assembly and the opinion of the Attorney of the United States for the Territory, will present the subject fully, and enable you to give whatever direction may be deemed proper.

I shall be gratified if the remarks I have made, shall in any degree facilitate your examination and decision of the subject.

I have the honor to be very respectfully, sir, your obedient servant.

J.J. CRITTENDEN.

–

[Editorial Begins] The Location Question.

In another column of to-day’s paper will be found a letter of Hon. John J. Crittenden, Attorney General of the United States, relating to the act of the late Legislative Assembly of this Territory contemplating the location and erection of the public buildings, elicited by a letter of Governor Gaines which likewise accompanies it. This whole proceeding is of an extraordinary character, and we propose to examine it from time to time, fearlessly and candidly, in no spirit of facetiousness or partisan opposition, but from an honest desire to discover the truth and the right.

It appears by the letter of the Attorney General that a written opinion upon the enactment was furnished the Governor by the Attorney for the Territory, and it is a little remarkable that this document was not also spread before the public. IT was by the Governor deemed essential to a proper understanding of the matter at Washington, and he can scarcely consider it less essential to a full understanding of it by the people of Oregon, before whom this dictum of the Attorney General is triumphantly spread by him through his two-penny organ, the Spectator. We trust this suppressed opinion will yet be forthcoming that the legislative Assembly and the people may have the benefit of all the light extant upon the subject, and that it may be placed upon record as a part of the history of the transaction.

We have said this proceeding was one of an extraordinary character, and to explain our meaning it will be necessary to go back to the commencement of the matter. Sometime last winter the Legislative Assembly enacted a law to provide for the location and erection of public buildings of the Territory. Whether this law is valid or invalid – whether it is in contravention of the organic act, or whether its passage involved an assumption of power delegated to the Governor is not our purpose to inquire. We leave that to be settled by the proper and competent authorities. But, immediately upon the passage of the act, a message from the Governor, disapproving of it and declaring it void, was officially read to the House of Representatives. Our organic law is materially different from that of the former Territories of the United States, (with the exception of Iowa.) the Legislative and Executive authorities are entirely distinct and separate, and act wholly independent of each other. The Governor of the Territory is not invested with veto power, and has no control over the connection with its Legislative Assembly, any more than the Judges or other federal officers have. He is not officially informed of their acts, and was not so informed of the passage of this. Then, whatever may be said of the course of the Legislature, whether right or wrought, there can be no difference of opinion among candid, unprejudiced men, in regard to that pursued by the Governor. It was uncalled for, indelicate, and impertinent, and we are not surprised that it was at the time vehemently denounced by members. Suppose one of the U.S. District Judges had transmitted such a document to that body, would not the members – both friends and foes of the enactment – with one accord have declared it irregular and intermeddlesome, and joined in administering a merited rebuke? Yet, in such case, the act would have been less unwarrantable, and the rebuke less deserved than in the case of the Governor. For our Judicial officers are presumed to be men of legal attainments, and capable of expounding and correctly construing laws, while no such presumption obtains in favor of the Governor. He was not officially informed of the passage of the act in question, and was not presumed to know that it had passed; and he had no right and no excuse for interfering with the duties and powers of others. If they had overstepped theirs, as he alleged, tit was no reason why he should do likewise.

An , finding himself – or being found by his friends – in this uncomfortable position, application is made to his political and personal friend, Hon. John J. Crittenden, for an “ official opinion” (See the Governor’s letter) defending his officious interference. Blundering at every step, he here commits another mortifying error in soliciting an official opinion form an officer who had no right to furnish such opinion. The duties of the Attorney General are defined by law to be “ to prosecute and conduct all suits in the Supreme Court in which the United States shall be concerned, and to give his advice and opinion upon questions of law when required by the President of the United States, or when requested by the heads of any of the departments touching any matter that may concern their department.” As the Governor is neither President of the United States, nor at the head of any of the departments of our government, he had no right to apply to the Attorney General for an “official” Opinion, and that office could not furnish him one without stepping aside from his legitimate duties. And he did not do it. He pointed out the Governor’s blunder by addressing his answer to the President. The Governor of Oregon addressed a letter to the Attorney General, and that functionary addressed his reply to the President of the United States, taking no notice whatever of the author of the letter.

Then, Mr. Crittenden’s “ statement,” as he terms his opinion is but the opinion of a lawyer, based upon an exparte statement, to sustain a partisan and personal friend, and as far as possible, to relive him from an unpleasant dilemma into which an ignorance of his duties or a characteristic super-serviceableness had plunged him.

–

*It is worth of note that while the Attorney General gives an opinion against the validity of the law, he is careful not to undertake to justify or excuse the officious conduct of the Governor.

Editorial, 1851

We might like to think that anonymous commentary about political affiars is a new phenomenon brought on by social media, but as this editorial illustrates, the practice is quite old. This unattributed editorial was published in the Oregon Statesman on September 19, 1851. Excerpts are reproduced below.

For the Oregon Statesman

Mr. Editor: – Where is the preset seat of government of Oregon is oftener asked than satisfactorily answered. By your permission, I beg through your columns to state may views on the subject. The law of Congress organizing the Territory left the capital temporarily to executive discretion, and its permanent location was authorized to be made by the first or any subsequent Legislative Assembly Oregon City was the place chosen by the Governor, and the Legislature, by an act passed in February, 1851, provided that Salem should thereafter be the Territorial seat of government. That statute, it is said, is disregarded by the Governor and other Federal officers, and treated as a nullity, although it remains on the statute book unrepealed, never adjudicated upon by any court, nor disapproved by Congress. In addition to this, it is also said, that certain members of the Legislative Assembly, who are required to meet at the Capital on the first Monday in December, being incited through the example set them by others high in authority, and it may be, in some degree, acted upon by local feeling, propose to go, for the purpose of discharging their Legislative duties, to Oregon City, rather than Salem, where the law, unrepealed and unadjudicated upon, requires them to assemble. In justification of this, it is alleged that the location act was passed in disregard of a certain restriction contained in the Organic law, and therefore not of any binding force upon either the Governor, members of the Legislature, or any body else. If this be correct, assuredly they are right, and it is immaterial what is the moving cause to such contemplated action, whether the example and counsel of men whose opinions they esteem, or local prejudice or honest conviction of duty. On the contrary, if such a position is not only unsound and actually subversive of the great foundation principles upon which our whole theory of representative and republican government is based, and will lead, if carried out, to a direct overthrow of the system which has so long and so well protected the just rights of all, it cannot and will not, I am sure, be persisted in when understood and such consequences made apparent. Let us then, to this end, look at the matter fairly, and if possible, included by the feelings to which it is to be feared quite too much of a war of crimination and recrimination has already given rise. In this spirit let us enquire where is the present actual seat of government; and where should members of the Legislature and Judges of the Supreme Court, all of whom are under the obligation of an oath to uphold and support the laws of the land, meet to transact the public business of their respective department? That is the real question. Where is the capital now, as a matter of fact, is the true enquiry, and not where should it be of right, or where may it be adjudged hereafter to be by some proper tribunal having rightful authority to pronounce what laws are and what are not binding upon the people. Let this distinction be kept constantly before us, and we shall not wader far from the path that may lead to a true answer.

The framework of our Territorial form of government, like that of the several States, resolves itself into three distinct departments, Legislative, Judicial and Executive, each independent of and a check upon the other, and all looking for a definition of their respective powers to a Constitution or Organic law. Each, in theory at least, is supposed to know and to keep within its proper sphere. The law-making power to prescribe the rules of action, the Judges or judiciary to adjudged their legality and binding obligation, and the Executive to enforce them. Each is sovereign within its own province…

If any act of the Territorial Legislature violates the provisions of the organic law, it is unquestionably null and void and the court can pronounce it so; but, because of a given or particular act may, in the opinion of learned gentlemen who do not constitute a court with legal authority to pass upon it, be deemed absolutely null and void, such opinions do not make it so, nor is any proof furnished thereby that it is so; for as we have seen, it is only through the judgement of the court that its nullity can be pronounced , and the proof of such invalidity be legally established.

The act locating the seat of government at Salem is thought by the Governor, by the Territorial District Attorney, by the Attorney General, and it is said by many others, to be unconstitutional. Well, be it so; but their opinions, however learned and respected, do not legally give it any such character, nor furnish any evidence whatever of its unconstitutionality….

All we mean to say on that point is simply that we understand the opinion of the learned Attorney General to amount to no more nor less than this – that, as a lawyer, he thinks the act in question unconstitutional; and I have no doubt meant to be no further understood; for it surely cannot be claimed for him, or any other eminent man, however high his station, that he can either make laws or destroy them. And when he says that all laws inconsistent with the provisions of the organic law are declared to be absolutely null and void, he means to say that the law of Congress, declaratory of the effect of such repugnant laws, is just what the Courts, having the power, when the question was properly before them, would pronounce, as the legal consequence of unconstitutionality. To understand him further than this, is to believe that he meant to counsel and advices and assumption of power rightfully belonging to another department – a thing we are unwilling to believe, no less from respect to the man than the absurd position it involuntarily forces him into as a high and respected public officer. If these views be correct then, how irrational is the pretense that the Executive, or individual members of the Legislature, may of their own head set at naught and practically NULLIFY a statue, which has never been brought to the judicial test to determine the proof of its validity or invalidity!

Cited References and Footnotes

[1] Unofficial records (WHC Research Library X2011.001.0100) show that by 1870, Portland’s population (not including East Portland stood at 8,293, whereas Salem’s population was a fraction of that at 1,139. Further looking back shows that Salem’s population in 1870, was only half of what Portland’s was a decade earlier (1860, Portland had 2,874 residents).

[2] The U.S. ratified the Treaty of Oregon with Great Britain in 1846. For more information see “The Oregon Question.” Smithsonian Institution. http://www.smithsonianeducation.org/educators/lesson_plans/borders/essay3.html

[3] There actually was an act introduced in Provisional Legislature in 1845 naming Oregon City as the capital. I do not know if it was adopted or not, but it would appear likely as the documented legislative meetings are held in Oregon City (see note 4). It is interesting to note that in the text of the act, the words “Oregon City” at the end are crossed out. Perhaps this was the beginning of the controversy? The document is in the microfilmed documents of the Provisional Government at the Oregon State Archives, Document number 1600. The microfilmed copy is barely legible. Here is my attempt at transcription of the preamble and the first section: “Be it enacted by the House of Representatives of the Oregon Territory. Section 1st. That for the present purposes of this Temporary Government, it shall be seated at Oregon City.”

[4] Bentson, William Allen. “Historic Capitols of Oregon…an illustrated chronology.” Salem: Oregon Library Foundation, 1987. Provides a succinct list of places that the early provisional government’s legislature met in Oregon City including the Methodist Mission building in Oregon City, and the Oregon City homes of Felix Hathaway, Theophilus Magruder, H.M. Knighton, and G.W. Rice.

[5] The Provisional Government was led by committees. The first committee was made up of David Hill who lived in what is now the Hillsboro Area, Alanson Beers a Missionary that lived at what is now Willamette Mission State Park, but later moved to Oregon City, and Joseph Gale who at the time seemed to call Oregon City (then known as the Falls) home. See Turnball, George S. Governors of Oregon. Portland: Binfords & Mort, 1959. Also George Abernethy who was elected Provisional Governor in 1845 was also based in Oregon City. Ibid.

[6] “An Act.” Oregon Statesman 4 Apr 1851 page 2.

[7] “An Act.” Oregon Statesman 4 Apr 1851 page 2.

[8]“An Act.” Oregon Statesman 4 Apr 1851 page 2.

[9] Oregon Statesman. 2 Dec. 1851, 3:1; 9 Dec. 1851, 2:2.

[10] Oregon Statesman. 24 Feb 1852, 2:4.

[11] “The Contest between the Whig Federal Officers and the People.” Oregon Statesman. 30 Dec 1851. 2: 1.

[12] Carey, Charles. General History of Oregon Portland: Binfords and Mort, 1971, 470-471

[13] “Letter from Gen. Lane – undoubted ratification of the location law…” Oregon Statesman 18 May 1852 2:7.

“The Question Settled.” Oregon Statesman 29 June 1852. 2:2. Joint resolution passes U.S. Congress unanimously.

[14] Oregon Statesman. 9 Jan 1855, 2:5; 16 Jan 1855, 3:2 – Bill in House to relocate the capital to Corvallis / Oregon Statesman 23 Jan 1855, 3:1 passed in House. / Oregon Statesman 30 Jan 1855 1:2 passed in the Council (2nd chamber of Oregon’s territorial legislature). Oregon Statesman6 Oct 1855, 2:5 – relocation of seat of government at

See also Oregon Statesman. 6 Feb 1855, 3:2; 3 Apr 1855, 3: 3 – 2:4; 30 Jun 1855, 2:4;

[15] Oregon Statesman 17 Dec 1855; 25 Dec 1855, 4:1.

[16] Oregon Statesman. 30 Dec 1855; 1 Jan 1856, 2:3.

[17] Bentson, 10.

[18] Oregon Statesman. 19 Aug 1856, 2:2; 22 Jan 1856, 2:6.

[19] Oregon Statesman. 7 Feb 1854, 2:1 – Bill in House to relocate capital to Eugene City.

Oregon Statesman. 29 Apr 1856 – Advertisement encouraging people to vote for Roseburg as capital

Oregon Statesman. 3 Feb 1857, 1:6 – Bill to remove seat of government o Portland, rejected. Again a motion 18 Jan 1859, 2:2.

[20] “Laws of the Oregon Territory” Oregon Statesman. 4 Mar 1856 4:1.

[21] “Mr. Avery Informs” Oregon Statesman 17 Jun 1856 2:2; Oregon Statesman. 26 Aug 1856 2:4

[22] Oregon Statesman. 15 Jul 1856 2:2; 15 Jul 1856 2:4.

[23] Article XVI. OREGON STATE CONSTITUTION 1857. Full text available on the Oregon State Archives Webpage:

http://bluebook.state.or.us/state/constitution/orig/const.htm

[24] Oregon Statesman. 2 Feb 1858; 21 Dec 1858, 2:5; 18 Jan 1859 2:1; 8 Oct 1860, 2:1; 20 Oct 1862, 2:2.

[25] Carey, 514.

[26] Oregon Statesman. 21 Oct 1856, 2:5.

Leave A Comment