A.C. Gilbert

In 1891, knowing his young son’s interest in magic, A.C. Gilbert’s father took him to the Reed Opera House to see “Hermann the Great,” one of the finest magicians of his time in America. Arrangements were made for the boy to go up onto the stage. At the end of performance, the magician said to his young admirer, “Don’t you wish you could do things like this?” Gilbert replied, “I can,” and demonstrated tricks he had learned from a magic kit he had won selling the children’s magazine Youth’s Companion.

Alfred Carlton Gilbert was born in Salem in 1884 at 700 Marion Street, the present site of the Congregational Church. As a boy he was responsible for tending the family cows, hauling firewood into the house, and trapping squirrels. He attended track meets at Willamette University, stimulating his interest in athletics.

In 1892, his family moved to Idaho where he organized a small athletic club for his friends. At a field day, he made winners’ medals out of the backs of his father’s old watches. At about this time he ran away from home to join a minstrel show: his father caught up with him when young Gilbert was only twenty miles away in Lewiston.

In 1900 the family returned to Salem. He attended Tualatin Academy where he continued his training in athletics and set world records for pull-ups and the running long jump. This led him to Pacific University and finally Yale University where he earned a medical degree.

To help pay tuition, he performed magic tricks he had learned as a child, often making as much as $100.00 a night. He also made his first boxed set of magic tricks which he sold for $5.00.

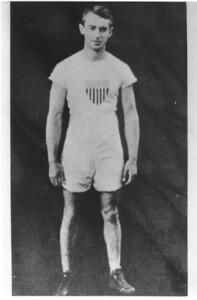

He was still training in athletics, setting a world’s record in pole vaulting, using a spikeless pole of his own invention. He qualified for the 1908 Olympics in London, but his victory there was disappointing. After a controversy with the judges about his use of a pole of his own invention, he used the same pole as his rival, E. T. Cooke – and still won. However, the judges ruled that Cooke had reached the same height in the preliminaries, and that the two should share the medal. Cooke graciously let Gilbert have the medal which was presented to him by Queen Alexandria of England.

Gilbert decided to direct his creative energy toward magic instead of pursuing a career as an athlete. His first business was in New Haven, Connecticut where he and his partner formed the Mysto-Manufacturing Company. His magic sets contained coin and handkerchief tricks, a decanter which changed one liquid into another, and an apparatus which allowed one to produce items from sleeves and pockets.

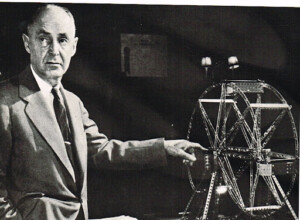

Early in 1911, while riding the train, he conceived of the Erector Set as he watched steel girders raising new power lines. One night, he and his wife cut out cardboard girders and worked with them until they fit together. A machinist converted the pieces into metal. Since his partner was not interested in this new idea, Gilbert marketed it himself at the Toy Fair of 1913.

The new company was renamed the A. C. Gilbert Company and in 1915 won the Gold Medal at the Panama Pacific Exhibition. He sold 30 million sets in the next two decades. The toy was not only popular with boys, but became useful to architects and scientists to build models of real structures and machines.

Meanwhile, in 1917, with the help of a chemist, Gilbert developed his chemistry set. A microscope set followed as another of his innovative educational toys. The American Flyer Train, developed in 1938 by W.O. Coleman, was bought by Gilbert who redesigned the cars to make them more realistic. By the end of the 1950s, Gilbert held 150 patents including ones for the small horsepower motor and the first low-cost fan sold in America.

His educational toys revolutionized the toy industry and his management of the company was just as progressive. He was one of the first to offer “coffee breaks” to his employees. He arranged programs of dancing and movies during lunch time and developed a personnel contract which protected jobs and allowed for conferences to discuss working conditions and other concerns. He emphasized the team-work concept and practiced it himself, often seen punching the time-clock and wandering informally around the plant with his pipe stuck in a pocket of his old gabardine suit.

After his retirement in the late 1950’s, the business went into decline and finally sold its trademarks to another company. Gilbert died in 1961, but his memory is very much alive and his unique concept of play as education is one that is universally accepted today. The A. C. Gilbert Discovery Village, a popular attraction to youngsters in his hometown as well as to tourists from around the world, is a lively monument to his creative genius.

This article originally appeared on the original Salem Online History site and has not been updated since 2006.

Leave A Comment