In the early 2000s, the City of Salem partnered with various heritage organizations and volunteers around the community to create an online portal looking at the history of Salem, Oregon. The original Salem (Online) History site had not been updated since 2006 and was taken offline in 2020. While not without its problems and errors, it was one of the few resources available with a comprehensive look at the history of the city. In 2022, the Willamette Heritage Center undertook the process of recreating the content of the website with the long-term goal of updating and improving the information provided. The site you are accessing today is a Beta site as we work on updating content. We hope to launch a more complete site by the end of 2022, but thought it might be helpful for folks to be able to access content as we work through it. Check back often to access more content!

Salem: The Basics

Salem is located in the Willamette Valley at the 45th Parallel, straddling the Willamette River and the county line between Marion and Polk Counties. Current city limits include a number of formerly separate communities including West Salem, Liberty, Fruitland, Chemawa, and Hazelgreen. It shares a border with separately incorporated city of Keizer, Oregon and the unincorporated communities of Hayesville, Middle Grove, and Four Corners.

Salem is the capital of Oregon and one of the state’s largest cities. This essay offers a brief overview of our community’s history.

The Kalapuya Native Americans were the first residents of what is now Salem. The Kalapuya traveled the Willamette River in dug-out canoes. Game, fish, fruits, and berries were plentiful in the Willamette River basin. It was a good place to gather.

Immigrants and pioneers from the Eastern United States also found a gathering place in the Willamette Valley, arriving by riverboat and wagon. They chose Salem as the territorial and state capitals and built industries and agricultural enterprises. Soon Salem became a center of government and commerce.

Today, when the “Willamette Queen” excursion riverboat travels along the city’s Willamette River shore, passengers view the city parks lining both sides of the river and the monuments to religion, commerce, and government which frame the horizon. Plentiful wildlife is still close by. Salem remains a gathering place for all.

The Kalapuya

Kalapuya Native Americans lived seasonally in the Salem area for more than 5,000 years. They gathered wild foods such as camas, wapato, and tarweed and hunted for deer and other game. They favored this part of the Willamette Valley for winter encampments.

While an estimated 17,000 Kalapuya once resided in the Willamette Valley, their population declined in the early nineteenth century because non-Native American explorers and traders from outside the valley brought Smallpox, Malaria, and other diseases for which the Kalapuya had little or no immunity. By the time the Kalapuya were moved to the Grand Ronde Reservation in the 1850’s, their group numbered fewer than 1,000. Descendents of the Kalapuya continue to live in the area and many are members of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde.

Trappers, Missionaries, and Settlers

The first European-Americans arrived in the Salem area in 1812. Working as trappers and food gatherers for the fur trading companies at Astoria, these early residents built a log dwelling and trapping house near the Willamette River. Today the exact location of these buildings is unknown.

Permanent American settlement of Salem began with the establishment of Jason Lee’s Methodist mission. Although Lee’s first mission was located north of Salem (in an area known today as Wheatland) he soon moved the facility to Mill Creek (near present-day Broadway and “D” streets.) He also built a sawmill. Lee’s house and several other pre-territorial buildings were preserved and are now open to the public on the grounds of the Willamette Heritage Center.

The Methodist missionaries organized the Oregon Institute, an institution of higher learning in 1842. The Institute was the forerunner to Willamette University, the first university in the West.

Early Government and Commerce

As the community matured, residents built the Salem’s first schools, churches, industries, and agricultural enterprises.

Salem formed its first public school district in 1855 and two years later the City of Salem received its first charter. Although the Methodist faith predominated in early Salem, soon a half dozen other religious denominations established congregations. During this same period, Marion County built its first wood-frame courthouse at High and State streets, a location still held by the present-day county courthouse.

Oregon became the 33rd member of the United States on February 14, 1859 and in 1864 voters reaffirmed the selection of Salem as its capital.

The governor, legislature, and Supreme Court conducted official business in several downtown Salem locations. The state’s first capitol, a wood-frame structure, was destroyed by fire in 1855 shortly after its construction. Construction on the second capitol (on the same site) did not begin until 1872.

Transportation, Commerce, and Communication

Transportation and communication expanded in the mid-nineteenth century with the arrival of the Hoosier, a steamboat, in 1851. The Hoosier traveled the Willamette River south to the city of Eugene and north to Oregon City, near Portland. The steamboat carried passengers, mail, and outbound freight including agricultural goods sold to miners in the California gold fields.

Inbound goods were unloaded at a dock on Pringle Creek near today’s Ferry and Commercial streets. Some of these goods were sold in the city’s first retail stores while other cargo was sent by ferry to settlements on the western shore of the Willamette River. The city’s first newspaper, the Oregon Statesman, which was moved to Salem in 1851, reported on the arrivals and departures of the steamboat.

As a river city, Salem was subject to seasonal flooding. One of the worst recorded floods occurred in 1861 when the Willamette River overflowed its banks, destroying nearby farms and food processing and manufacturing plants.

Salem’s population grew to 2,500 by 1880. The city’s growth was accelerated by the expansion of agriculture and logging, and the continued development of national and international markets. Food processing plants and woolen mills, such as the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, formed the base of Salem’s economy. The state’s first agricultural fair, a forerunner to today’s Oregon State Fair, had been held about twenty years earlier, in 1861.

Telegraph service had arrived in Salem in 1864 and a railroad line to Portland was completed in 1872. Salem’s first bridge across the Willamette River was built in 1886. The city’s economic growth continued into the 1880s and 1890s, although it stalled during the severe 1890 flood and the national economic depression of 1893 to 1897.

During this same time, Salem’s streets were improved and its water and sewer systems were installed. Chemawa Indian School, a federal boarding school for Native American youth, moved to an area just north of Salem in 1885.

Dynamic Nineteenth Century

Many influential people lived in Salem during the last half of the nineteenth century. Some of the city’s leading citizens built large homes along Court Street between downtown and the capitol, while others preferred more rural areas. In 1877 Asahel Bush, a banker and newspaper publisher, built his elegant home just south of downtown in what is today Bush’s Pasture Park. Nearby, during the 1890’s, Dr. Luke Port built his beautiful Queen Anne-style home, a mansion known today as Historic Deepwood Estate.

Other notable Salem residents of the time include Myra Albert Wiggins, an internationally known professional photographer; future United States president Herbert Hoover, then employed as an office boy for the Oregon Land Company; and Ruben Sanders, an award-winning Native American athlete who played and coached at Chemawa Indian School.

Minority Residents

At the outbreak of the U. S. Civil War, Salem residents were divided over which side to support. While most residents supported the Union, they also did not want African-Americans living among them. Although no military battles were fought here, at least one stick-and-stone brouhaha took place over issues related to the war.

The several hundred Chinese-American residents of Salem were limited to living in a two block section of the city’s downtown. Most were employed in low-wage jobs, the only employment available to them.

Several generations of Japanese-Americans, who farmed at Lake Labish just north of Salem, were removed from their homes and sent to detainment camps in 1942 at the outbreak of World War II. Most never returned to Salem.

Mexican and Mexican-American families moved to Salem to do farm work during World War II. After the war many became permanent Willamette Valley residents.

Becoming a Modern City

Women, who had won the right to vote in 1912, were active in the political and cultural life of the city during the early twentieth century. The Salem Woman’s Club appointed a library committee in 1903 and operated the city’s first public library, eventually ceding its ownership to the City of Salem. Members of the Woman’s Club were instrumental in securing library construction funds from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie a decade later. In 1916, Salem’s women helped establish Deaconess Hospital, a forerunner to today’s Salem Hospital.

High school instruction was first offered to Salem children in the early 1900’s. In 1907, the city’s first high school opened at High and Marion streets in downtown Salem. This building was later demolished, making way for the Meier and Frank Department Store.

Largely due to an annexation in 1903, Salem’s population tripled from 1900 to 1920. Its municipal government began paving the community’s streets in 1907, with five blocks of Court Street its first project. Paved streets had become a necessity after the arrival of the city’s first automobile in 1902.

Salem took the nickname “The Cherry City” in 1903 in recognition of its food processing industry and for many years the city celebrated an annual Cherry Festival.

The 1920’s and 1930’s

The 1920’s marked a decade of rapid change. In industry, the Oregon Pulp and Paper Company began operations near Pringle Creek in 1920. Medical services expanded with the opening of Salem General Hospital, and in 1923 the city established its first full-time municipal fire department.

By the time the last streetcar ceased operation in 1927 (after nearly 40 years of transporting Salem residents) the city had more than 35 miles of paved streets. Two major downtown buildings, the Elsinore Theatre and the Livesley Building (today’s Capitol Center) both opened in 1926. The city’s first radio stations also began broadcasting in the 1920s.

In 1930, Salem residents voted for a municipal water system and by 1935 had purchased the private water works which had served the city. Although telephone service had been available since the late nineteenth century, Salem’s first dial telephone system was installed in 1931. Another technological innovation, the police radio, arrived in Salem in 1933.

The capitol was destroyed by fire on April 25, 1935 despite the efforts of fire crews from throughout the Willamette Valley. With the help of funds from the federal government, Oregon built a new capitol during the next three years, topped by a twenty-two foot bronze figure with gold overleaf called the “Oregon Pioneer.” A new State Library opened across Court Street a year later.

During the 1930’s Salem residents watched the activities of several national politicians with strong connections to their city. Herbert Hoover was the President of the United States from 1929 to 1933, while Charles McNary was a leading United States Senator and Vice Presidential nominee in 1940. Hollis Hawley was a leader in the United States House of Representatives. Locally, Oregon Statesman publisher Charles Sprague served as Oregon Governor from 1939 to 1943.

The 1940’s and post-World War II

Salem celebrated its centennial in 1940. The city’s population was 30,908. Although the Great Depression of the 1930s forced many residents from their jobs, Salem’s economy was on the rebound as the new decade began.

Salem’s economy continued to be strong during World War II as businesses turned their production to the war effort. Nearby Camp Adair, a military training facility, brought many soldiers to Salem.

Residents celebrated the end of World War II for two days, but also recalled the hundreds of fellow Salem citizens who were injured or killed during the war.

The postwar years saw the decline of Salem’s downtown area. Sulfurous odors from the paper mill penetrated nearby homes. Busy railroad crossings and other traffic problems made it easier to shop in the suburban retail areas. Construction of Interstate 5, a highway on the east side of the city, accelerated the changes.

Salem adopted the City Manager-Council form of government in 1947 with J. L. Franzen taking office as the first Salem city manager. In 1949 Salem annexed the adjoining community of West Salem, an independent city since its incorporation in 1913. With the annexation Salem straddled the eastern and western shores of the Willamette River; its citizens resided in Marion and Polk counties respectively.

During the 1950’s Salem improved and extended crucial utilities needed in a growing city, including the sewage treatment system and natural gas connections. The Marion County Courthouse, still in use today, was built in the mid-1950’s and the old courthouse demolished.

Salem received its first television signals in 1952 and in 1953 the Capital Journal and Oregon Statesman newspapers merged business operations but continued as separate publications. By the mid-1980’s these newspapers would merge into one newspaper, renamed the Statesman Journal.

The Detroit Dam in the mountains east of Salem was constructed during the 1950s. Detroit Dam and other dams on the Willamette River and its tributaries reduced the chance of flooding and encouraged development in low lying areas such as Keizer, an area north of the city.

In 1949, the Salem Art Association staged the first Salem Art Fair in Bush’s Pasture Park, a recent addition to the city’s park system. The Art Fair continues to be a popular Salem event.

The 1960’s and 1970’s

Salem garnered national attention and received the coveted “All-American City” award in 1961. The award recognized Salem for its efforts in inter-government and government-school cooperation during the 1950’s.

The 1960’s and 1970’s brought natural disasters to the city. A heavy windstorm on Columbus Day 1962 caused extensive damage as did a flood during December 1964. The Marion Hotel, a longtime downtown landmark, burned in 1971.

Although many inner cities deteriorated during the 1960’s and 1970’s, Salem’s efforts resulted in a revitalized downtown. Streams, once hidden beneath streets and behind factories, were uncovered. New parks, plazas, footpaths, and bicycle lanes were constructed.

The downtown received a new look with the construction of a shopping complex, anchored by Nordstrom, a major retailer. An adjoining mall facility was built in the 1990’s and the complex was renamed Salem Center. It soon became a flagship for downtown businesses and services. Marion County joined the Salem Mass Transit District to build Courthouse Square, a centralized downtown transit center and county office facility which opened in 2000.

City Hall, formerly at Chemeketa and High streets, was torn down in 1972 and a City Hall/Civic Center was constructed on the southern edge of downtown. A new Public Library and a central Fire Station were included in the modern complex.

Educational opportunities for local residents expanded with the opening of Chemeketa Community College 1970.

The 1980’s and beyond

Salem’ s population had climbed to 96,830 by 1980 and two decades of rapid change had begun.

Large national retailers such as Costco, Shopko, Wal-Mart, Target, and Home Depot recognized Salem’s market potential and opened outlets in suburban Salem.

Salem’s roots in the lumber and textile industries gradually gave way to high technology. In 1989, Siltec, a computer chip manufacturer, established a facility. By 1996, the facility had grown to more than one million square feet of manufacturing and had been renamed Mitsubishi Silicon America. II Morrow, a successful local high technology business was purchased by United Parcel Service. Salem’s diversification into electronics and metal fabrication was praised by Oregon Business magazine.

The city’s ethnic diversity flourished during the 1980’s and 1990’s. Salem’s Hispanic and Asian communities grew and migration from the former Soviet Union brought numerous Eastern European families to Marion County. Tokyo International University of America, a Japanese college, opened a Salem campus in conjunction with Willamette University in 1989. Restaurants and retail stores catering to Salem’s immigrant communities opened for business.

Salem citizens continued their active involvement in several neighborhood associations. Crime prevention, parks, and livability were issues addressed by the neighborhood associations. During the 1980’s, the Court-Chemeketa and Gaiety Hill-Bush’s Pasture Park neighborhoods were designated National Historic Districts.

Although the city no longer celebrated its Cherry Festival, a new event, the Festival of Lights parade, attracted thousands of spectators to downtown Salem each December. Riverfront Park was dedicated in 1998, nearly fifty years after its initial plans were discussed. A carousel, featuring horses and other whimsical fixtures carved by local residents, opened in 2001.

Salem continues to be the heart of Oregon state government and a center for finance, retail, and services in the mid-Willamette Valley. New housing developments cover hillsides in West and South Salem which were once occupied by orchards and fields. In 2002, Salem surpassed Eugene to become Oregon’s second most populous city. Salem citizens, like those before them, will continue to create a new Salem.

Researched and written by Monica Mersinger

Edited by Kyle Jansson, Marion County Historical Society

Bibliography:

Bentson, William Allen. Historic Capitols of Oregon…an Illustrated Chronology, 1987.

“Chronology of Significant Events” Statesman Journal, October 26, 1990.

Miller, Robert H. “Library Development Plan,” Salem Public Library, January 1997.

Postrel, Dan. Statesman Journal, July 23, 1997.

Strozut, George. “Salem History,” pp. 13-39. Unpublished manuscript

Note this information has not been updated since 2006.

Historia Breve |

| Salem es la capital de Oregon y es la segunda ciudad más grande del Estado. Este ensayo ofrece una descripción breve de la historia de nuestra comunidad.

Los Kalapuyas fueron los primeros residentes del lugar que ahora es Salem. Los animales silvestres, los peces, las frutas y las bayas abundaban en la vecindad del río de Willamette. Con estas condiciones tan propicias, éste era un buen lugar para establecerse. Inmigrantes y pioneros del oriente de los Estados Unidos también encontraron un lugar propio para establecerse en el valle de Willamette, arribando hasta aquí por medio de barcos y bagones. Ellos escogieron Salem como la capital del Estado y construyeron industrias y empresas agrícolas; de esta manera, rápidamente Salem llegó a ser un centro de gobierno y de comercio. En la actualidad, cuando la excursión en barco “Willamette Queen” viaja a través del río de Willamette por las orillas de la ciudad, los pasajeros pueden observar los parques en ambos lados del río, los monumentos religiosos, el comercio y los edificios de gobiernos, los cuales enmarcan el horizonte. La fauna abundante y tranquila todavía existe. Salem sigue siendo un lugar propio para establecerse. Los Kalapuyas Cuando cerca de 80,000 Kalapuyas vivían en el valle de Willamette, su población se vió disminuida en los primeros años del siglo XIX, debido a que exploradores no nativos y comerciantes, trajeron desde fuera del valle enfermades tales como smallpox y la malaria, para las cuales los Kalapuyas tuvieron muy poca o ninguna inmunidad. En 1850 un grupo de menos de 1,000 Kalapuyas fueron llevados a la reservación Grand Ronde. Sus descendientes siguieron viviendo en el área y muchos son miembros de las tribus confederadas de la reservación Grand Ronde. Los Europeos-Americanos El asentamiento permanente de americanos en Salem se inició en 1840 con el establecimiento de la misión metodista de Janson Lee. Lee y sus colegas también construyeron un aserradero en el riachuelo del Molino (cerca de lo que ahora son las calles D y Broasway). Actualmente, la casa de Lee y muchos otros edificios pre-territoriales se localizan en las tierras del Museo del Molino de la Misión de Salem. Los misioneros metodistas fundaron el Instituto de Oregon en 1842. Este Instituto fue el precursor de la Universidad de Willamette, la primera Universidad del Oeste. Una Nueva Ciudad Aunque la fe metodista predominaba en el naciente Salem, pronto una media docena de otras denominaciones religiosas establecieron sus congregaciones aquí. La transportación y las oportunidades de comunicación se expandieron a mediados del siblo XIX con el arribo del primer barco, el “Hoosier”, en 1851. Los barcos tales como el “Hoosier” navegaban sobre el río de Willamette al sur de la ciudad de Eugene y al norte de la ciudad de Oregon cerca de Portland. Los barcos transportaban el correo, los pasajeros y principalmente los fletes (transporte de cargas). La mayoría de los fletes que salían de Salem, principalmente bienes agrícolas, eran enviados a California para alimentar a los mineros en los campos de minas de oro. Los fletes que llegaban eran descargados en una dársena en el riachuelo cerca de las calles Commercial y Ferry. Las cargas se vendían en las primeras tiendas de ventas al minoreo de la ciudad, cerca de la dársena o eran enviadas por el transbordador a los colonizadores en la costa occidental del río de Willamtte. Las llegadas y las salidas de los barcos de carga se reportaban en el primer diario de la ciudad, el Oregon Statement, el cual fue traído a Salem en 1851. Debido a que era una ciudad de río, Salem estaba sujeta a inundaciones estacionales. La peor inundación registrada ocurrió en 1862, cuando se desbordaron los bancos del río Willamette, destruyendo las plantas de procesado de alimentos, las empresas de manufactura y las granjas cercanas. La Estadidad Las décadas de los 60 y los70 del siglo XIX. Un telégrafo se instaló en Salem en 1864 y una línea ferroviaria a Portland se construyó completamente en 1872. La población de Salem creció a 2,500 habitantes en 1880. El crecimiento de la ciudad se aceleró con la expansión de la agricultura y las industrias de explotación forestal. Las plantas del procesamiento del alimentos y los molinos de lana, tal como el molino de Thomas Kay, constituyeron la base de la economía de Salem. Las décadas de los 80 y los 90 del siglo XIX El primer puente sobre el río de Willamette para cruzar hacia la Villa del West Salem fue construido en 1886. Mientras que dicho puente estimulaba el desarrollo de la ciudad, la presencia del Gobierno del Estado proporcionaba una fuerza estabilizadora en la economía local. En este tiempo, las calles de Salem fueron remodeladas y se instalaron los sistemas de agua y alcantarillado. La escuela india Chemewa, una escuela federal construida con tablas para nativos americanos jóvenes, fue situada en un área justo al norte de la ciudad de Salem en 1885. Mucha gente dinámica vivió en Salem durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Algunos de los ciudadanos más prósperos de la ciudad construyeron casas grandes a lo largo de la calle Court, entre el centro de la ciudad y el Capitolio del Estado, mientras que otros prefirieron las areas más rurales en las afueras de la ciudad de Salem. Por ejemplo, Asahel Bush, un editor periodístico y banquero, construyó en 1877 una elegante casa justo al sur de la ciudad, en lo que ahora se conoce como el parque Bush. En fechas cercanas, durante los años 90, el Dr. Luke Port construyó su hermosa casa al estilo de la Reina Anne, una mansión hoy conocida como la casa “Deepwood”, una propiedad histórica del Estado. Otros residentes exitosos de Salem de este tiempo son Myra Albert Wiggins, una fotógrafa profesional internacionalmente reconocida; Herbert Hoover, quien sería futuro Presidente de los Estados Unidos, entonces empleado como un office boy para la Oregon Land Company; y Ruben Sanders, un nativo americano y atleta victorioso, quien fue jugador y entrenador en la escuela india Chemawa. Pero no todos los residentes de Salem compartieron estas oportunidades de éxito. Muchos cientos de Chinos-Americanos estaban limitados a vivir en una sección de dos cuadras en el centro de la ciudad y a trabajos de bajo sueldo. Un nuevo siglo Debido a una anexión en 1903, la población de Salem se triplicó de 1900 a 1920: más crecimiento estaba previsto para la ciudad capital. El distrito escolar de Salem comenzó la instrucción de la preparatoria a principios del siglo, entre 1900 y 1907 una preparatoria nueva abrió sus puertas entre las calles High y Marion (el sitio donde se localiza hoy en día la tienda departamental Meier and Franck). En 1907 la ciudad de Salem empezó la pavimentación de las calles. Las cinco cuadras de la calle Court fueron su primer proyecto. Este proyecto se hizo más necesario debido al arribo del primer automovil en 1902. En 1903 Salem obtuvo el apodo de la “Ciudad de la cherry” como un reconocimiento a la bien conocida industria de procesado de alimentos en esta comunidad. La década de los 20 del siglo XX El año 1926 trajo consigo las grandes aperturas del teatro Elsinore y del Edificio Livesley, el cual ahora es conocido como el Centro Principal. Por el año de 1927, el último tranvía de la ciudad cesaba sus operaciones después de transportar durante 40 años a los residentes de Salem. Para este tiempo la ciudad ya había pavimentado más de 35 millas en calles. Durante esta década las estaciones de radio iniciaron también sus transmisiones. La década de los 30 del siglo XX El primer sistema de radio para la policía entró en acción en 1933. Este sistema quedó inhabilitado la noche del 25 de abril de 1935, cuando el Capitolio del Estado fue destruido por el fuego a pesar de los esfuerzos de tripulaciones de bomberos a través del valle de Willamette. Con la ayuda de fondos federales de gobierno, Oregon construyó un nuevo Capitolio durante los siguientes tres años. El Capitolio fue adornado en su parte superior con una figura de bronze de 22 pies chapeada en oro, llamada el “Pionero de Oregon”. Un nuevo edificio de la biblioteca del Estado habrió sus puertas un año más tarde sobre la calle Court. Durante los años 30, los residentes de Salem observaron las actividades de muchos políticos nacionales quienes tenían orígenes en esta ciudad. Herbert Hoover fue Presidente de los Estados Unidos de 1929 a 1933. Charles McNary fue un dirigente del Senado de los Estados Unidos y estaba nominado para la Vice-Presidencia en 1940. Hollis Hawley fue un lider en la Casa de Representantes de los Estado Unidos. Charles Sprague, editor del periódico Oregon Statement sirvió como Gobernador de Oregon de 1939 a 1943. El Salem de la década de los 40 y posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial La economía de la ciudad continuó fortaleciéndose conforme los negocios encaminaban su producción hacia los esfuerzos de la guerra. La cercanía del campo Adair trajo a muchos soldados a la ciudad. Las familias Japonesas-Americanas, quienes cultivaron en el lago Labish justo al norte de Salem, fueron dehalojadas de sus hogares y enviadas a campos de concentración en 1942. Muchos de ellos nunca regresaron a Salem. Durante este mismo tiempo, gran cantidad de familias mexicanas llegaron a Salem para ayudar con los trabajos de las granjas. Muchas de estas familias llegaron a ser residentes permanentes de Salem y otras de las comunidades del valle de Willamette. Los residentes de Salem celebraron el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial durante dos días, pero también recordaron a centenares de residentes de Salem quienes fueron heridos y matados durante esta guerra. Los años de la postguerra vieron el decaimiento del área del centro de la ciudad de Salem. El centro de la ciudad había perdido su aspecto agradable por muchas razones, incluyendo los olores sulfurosos del molino de papel. Los residentes decidieron hacer sus compras en los nuevos centros suburbanos de ventas al minoreo que se habían desarrollado recientemente, en lugar de viajar al centro de la ciudad con sus congestionados cruces de ferrocarril y otros problemas de tráfico. Salem adoptó el Ayuntamiento como forma de gobierno en 1947, teniendo a J.L. Franzen como primer Presidente del ayuntamiento. En 1949 se adjuntó el West Salem a la ciudad de Salem, una comunidad en el lado occidental del río de Willamette, la cual se había fundado en 1913. La ciudad mejoró notablemente y dispuso de servicios cruciales en los años 50, incluyendo un sistema de tratamiento de aguas residuales, las conexiones de gas natural y las mejoras del sistema de agua. La construcción del Palacio de Justicia del Condado Marion se inició en 1953. Salem recibió su primera señal de television en 1952 y en 1953 los periódicos Capital Journal y Oregon Statement unieron sus operaciones de negocios, pero continuaron como publicaciones separadas. El dique de Detroit que se encuentra sobre la región de las montañas al este de Salem fue contruido durante los años 50. Este dique y otros poryectos para el control de inundaciones redujeron los riesgos de inundación y alentaron el desarrollo en areas de más bajo relieve como Keizer, justo al norte de Salem. En 1949, la Asociación de Arte de Salem preparó la primera feria de arte en el parque Bush (Parque del pasto del arbusto), el cual había sido agregado al sistema de parques de la ciudad. Salem ganó el codiciado premio “All- American City” en 1961, esto debido principalmente a la colaboración en las escuelas de gobierno y a otros esfuerzos realizados en la época de la post guerra. Los años 60 y las siguientes décadas Salem comenzó a reforzar sus areas del centro de la ciudad en los años 60 y los 70. Las corrientes fueron destapadas una vez que se habían escondido bajo las calles y detrás de las fabricas. Los nuevos parques, las plazas, “cacading pools”, vías peatonales y vías para ciclistas fueron construídas al lado más al sur del centro de la ciudad. Muchos de los edificios históricos de la ciudad fueron conservados con la apertura del Museo del Molino de la Misión. Para 1970 la población de Salem había crecido hasta 68,309 habitantes. El hotel Marion, un edificio de larga vida, objeto representativo del centro de la ciudad, preferido por los legisladores y otros visitantes, se incendió en 1972. Unas nuevas oficinas municipales fueron construidas dentro del complejo del Centro Cívico, el cual también incluye la biblioteca pública y la estación central de bomberos. Los esfuerzos por crear un parque a lo largo del río de Willamette cerca del centro de la ciudad ganaron fuerza. Las oportunidades educacionales se ampliaron con la fundación del colegio comunitario Chemeketa en 1970. Para 1980 la población de Salem había alcanzado los 96,830 habitantes. En ese año, el Capital Journal, un periódico vespertino suspendió sus operaciones y el periódico matutino fue renombrado como el Statement Journal. Una recesión económica de 1979 a 1986 incrementó el desempleo, pero nuevos comercios y servicios de yardas proporcionaron un soporte y las industrias de la ciudad y las ventas al minoreo cambiaron. Durante los 80 la compañia Nordstrom, uno de los principales detallistas nacionales de alta escala, abrió su primera tienda en Salem, impulsando de esta manera a otros negocios del centro de la ciudad. También la compañia Siltec, un fabricante de ships de computadora, propocionó facilidades de desarrollo para la comunidad. Para 1996 la compañía Siltec había crecido a más de un millón de pies cuadrados en su planta de manufactura y se convertía en lo que ahora es Mitsubishi Silicon America. Morrow II, uno de los negocios locales de alta tecnología, especializado en sistemas de trazado de vehículos, floreció y fue comprado por la United Parcel Service. Las técnicas iniciales que Salem utilizaba en la madera, en el textil y en las industrias agrícolas daban paso gradualmente a la tecnología de alto nivel. En 1990 la revista Oregon Business premió a Salem por la diversificación en la fabricación de la electrónica y del metal. Así como la composición étnica y racial de Salem había cambiado con la llegada de los primeros Americanos-Europeos en los primeros años de 1800, la configuración étnica de la ciudad cambiada durante los años 80. Su población Hispana creció en un 111%, aumentando de 3,110 hasta 6,588; mientras que su población asiática creció en un 169%, aumentando de 957 hasta 2,577 habitantes, como resultado de una entrada constante de Vietnamitas y otros asiáticos a partir del conflicto de Vietnam de los años 60. La Universidad Internacional de Tokio también abrió un campus en Salem en 1989. La migración proveniente de lo que antes fuera la Unión Sovietica se incrementó para 1988. Más de 1,000 familias Rusas se movieron al Condado Marion para 1992. La población total de la ciudad se incrementó en un 21%. Durante los años 80, Court-Chemeketa y el área de las colinas vecinas del Parque Bush fueron designados como distritos históricos nacionales. La A.C. Aldea del Descubrimiento Gilbert abrió también sus puertas al público durante este tiempo. Una larga dedicación de una década para mantener vital el centro de la ciudad durante los años 90, tuvo como resultado el centro de Salem con sus puentes de cielo enlazando las tiendas más grandes, un complejo de cinemas adyacente y las estructuras para estacionamiento de vehículos. Este movimiento creó un centro de paseo regional, mejor conocido como “mall”. Las construcciones Frederick y Nelson en las calles Chemeketa y Liberty fueron renovadas para ocuparse por negocios de ventas al minoreo y por oficinas, teniendo una reapertura como la Plaza Libertad en 1996. Un festival de luces en el centro de la ciudad es un atractivo visual para miles de paseantes durante el mes de diciembre. Los detallistas de descuentos más grandes tales como Costco, Shopko, Wal-Mart y Home Base llegaron a Salem a principios de 1995. La participación del gobierno en la economía de Salem sufrió un revés en noviembre 1990, cuándo votantes aprobaron la “Ballot Measure 5”, una medida para la limitación del impuesto sobre la propiedad. Esta medida redujo los servicios del gobierno local y solicita al estado que proporcione una porción más grande para el financiamiento de las escuelas. Otras medidas adicionales en la limitación de los impuestos fueron consideradas por los votantes a lo largo de esta década. La ciudad de Salem completó la creación del parque Riverfront en 1998 casi 50 años después de la primera sugerencia de su creación. Al iniciarse un nuevo siglo con el año 2000, Salem había cambiado dramáticamente a partir de su fundación desde hace más de 150 años. Algunos empleados de la ciudad, del Condado y del Gobierno del Estado estaban en sus lugares de trabajo la ultima noche de 1999, vigilando que los servicios del gobierno operados con computadora no fueran afectados por “glitches” de las computadoras con el cambio del milenio. El Distrito Escolar Salem-Keizer, formado en los años 50, comenzó la construcción de su sexta escuela preparatoria también por este tiempo. El condado Marion y el Distrito de Tránsito Masivo de Salem se unieron para construir el edificio “Courthouse Square”, el cual consiste en un centro centralizado de tránsito y oficinas del Condado. El Director de la ciudad Larry Wacker se jubiló después de siete años en el trabajo y 33 años del servicio a la ciudad. Al iniciar la construcción de un carrusel en el parque Riverfront, se acordó también representar animales tallados en madera por residentes locales. El Hospital de Salem dió a conocer sus planes para duplicar su tamaño con un proyecto de 250 millones de dólares, siendo cubierto durante los próximos 10 años. Existen actualmente centenares de iglesias y docenas de denominaciones religiosas. Salem ahora abarca las porciones tanto del Condado Marion, como del Condado Polk a lo largo de las orillas del río de Willamette. El río es el punto focal del desarrollo en el valle, con un 70% de sus residentes viviendo dentro de 20 millas sobre los bancos del río. Las proyecciones de 1999 indicaron que la población de Salem es de 128,595 habitantes. En la actualidad, Salem sigue siendo un lugar propio para establecerse. Inestigación y redación: Monica Mersinger. Edición: Kyle Jansson, Sociedad Histórica del Condado Marion. |

Topics

Community

Education

For an overview of this history of Salem School Names, see Fritz Juengling’s Article in Willamette Valley Voices pg 18.

Colleges and Universities

Chemeketa Community College

Corban University

Tokyo International University of America (1989)

Willamette University

Federal Schools

Chemawa Indian School

Winema School

Parochial

Blanchet School (1995)

Concordia Lutheran School (1996)

Immanuel Evangelical Luthern School (2002)

Livingston Junior Academy (1898)

Sacred Heart Academy (Catholic)

Sierra High School (Catholic)

St. Joseph (1941)

St. Paul’s School — Episcopal (c.1887-1889)

St. Vincent de Paul (1925)

Queen of Peace (1964) Catholic

Western Mennonite School (1945)

Public Charter Schools

Jane Goodall Environmental Middle School

Professional and Trade Schools

Capital Business College

Merritt Davis Commercial Business College

Private Schools

Abiqua (1993)

Salem Academy (1945)

Sonshine (1980)

Salem Keizer Public Schools – Elementary

Auburn (1955)

Baker (1951)

Brush College (1905)

Bush (1936)

Candalaria (1955)

Chapman Hill (1986)

Clear Lake (1892)

Cummings (1953)

Englewood (1910)

Fay Wright (1963)

Forest Ridge (2002)

Four Corners (1949)

Fruitland (1936)

Grant (1908)

Gubser (1977)

Hallman (2001)

Hammond (2001)

Harritt (2003)

Hayesville (1909)

Hazel Green (1954)

Highland (1913)

Hoover (1952)

Kalapuya (2011)

Keizer (1973)

Kennedy (1964)

Lamb (2001)

Lee (2002)

Liberty (1908)

Mary Eyre (1977)

McKinley (1915)

Middle Grove (1947)

Miller (2000)

Morningside (1953)

Myers (1973)

Optimum Learning Environment Charter School (2002)

Pringle (1937)

Richmond (1912)

Rosedale (1952)

Salem Heights (1938_

Schirle (1974)

Scott (1977)

Sumpter (1978)

Swegle (1923

Valley Inquiry Charter School (2005)

Washington (1949)

Weddle (2001)

Yoshikai (1994)

Salem Keizer Public Schools – Middle Schools

Claggett Creek (2001)

Crossler(1995)

Goodall (2000)

Houck (1995)

Judson (1957)

Leslie (1927)

Parrish (1924)

Stephens (1995)

Straub (2011_

Waldo (1957

Walker (1961)

Whiteaker

Salem Keizer Public Schools — High School

Barbara Roberts (1996)

Early College High School (2006)

McKay (1979)

McNary (1965)

North Salem (1936) originally Salem High School

South Salem (1954)

Sprague (1972)

West Salem (2001)

State Schools

Farrell (1914) — A.K.A. State Industrial School for Girls and Later Hillcrest.

Oregon School for the Blind

Oregon School for the Deaf (1870)

Anniversaries

Salem Centennial (1940)

Salem Sesquicentennial (1990)

Annual Events

Annual Labor Day Hike

Historic Gardens Calendar

Salem Easter Traditions

Salem’s Outdoor Christmas Tree

Military Actions

Battle of the Abiqua

World War II

Iranian Hostage Crisis

Church Histories

- First Baptist Church

- First Christian Church

- First Church of Christ Scientist

- First Congregational Church

- First Presbyterian Church

- Jason Lee United Methodist Church

- Kingwood Bible Church

- Salem Alliance Church

- Salem Mennonite Church

- St. Joseph Church

- St. Mark’s Church

- St. Paul’s Church

- St. Paul’s AME Church

- St. Timothy Church

- St. Vincent de Paul Church

- United Methodist Church

Entertainment

Crescent Probe by James Hansen. Photo Source: Unknown – published in the 2006 Salem Online History Project

Art Articles

Carroll L. Moores and Rodin’s Venus

City of Salem Civic Center Art Collection

Hallie Ford Museum, Willamette University

Salem Federal Art Center

Salem Art Association

Cherry Fair

Emancipation Jubilee Celebrations

Lunar New Year

Salem Art Fair

Salem State Fair

World Beat Festival

General Entertainment History

Theaters

Environment

Industry

Agriculture Articles:

Cherries

Dairy

Great Oregon Steam-up

Flax

Flowers

Hops

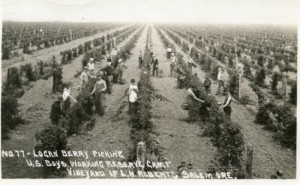

Loganberries

Lumber

Marionberries

Prunes

Turkeys

Wheat

Wool

Loganberry picking in vineyard of L.H. Roberts, Salem, Oregon. WHC Collections 2011.006.0485. This photo had to have been taken sometime after 1917 as it features a WWI era labor program called “U.S. Boys Working Reserve.”

Agriculture Overview

The bounty of the land in and around Salem was evident to the Kalapuya people who frequented seasonal homes in and around Salem for thousands of years. Prescribed burning by the Kalapuya and other Native peoples of the Willamette Valley created the open oak savannah in the prairie, and evidence suggests, among other things aided in the cultivation of oak trees for acorns production and gathering and grasslands for proliferation of game.

Although they might not have recognized it as a carefully cultivated landscape, the open prairies also appealed to many Euro-American settlers, who also prized the rich alluvial soils in the valley around the Willamette River and ice age flooding.

Lumber and farming became the first commercial enterprises as the farmers established saw and grist mills on Mill Creek. Missionary Jason Lee built his mill near the fork of today’s Broadway and High streets in what they considered North Salem. A historical marker marks the site now across from Boon’s Tavern. These mills served not only the builder but also neighbors who relied on them to grind the wheat and saw the trees which they had cleared from their lots.

With naturally cool but rarely freezing temperatures, abundant rainfall and fertile valleys, Oregon’s climate favored certain crops such as strawberries, timber, loganberries, filberts (hazel nuts) cherries, marionberries, hops, nursery stock, grass seed, and prunes. Canneries and mills sprang up to process the harvests and resources produced in the valley. Rich soils provided abundant feed for the raising of cattle and sheep. Meat packing and wool, flax, wheat, and lumber mills were developed to process the bounty. Agriculture remains a vital part of the commerce of the Salem community in the 21st century.

Today acres and acres of wheat fields stretch on both sides of the route from Salem to the coast. Hops were another primary crop which for a period made a strong showing and is still grown around Salem.

Source Materials:

Researched by Joan Marie “Toni” Meyering

Written by Joan Marie “Toni” Meyering and Monica Mersinger

Updated 2020

Accountants

Book stores

Canneries

Car Businesses

Clothing and fabric Stores

Construction and Architecture

Arbuckle Costic Architects

Pumilite Building Products

Walling Companies

Dairy

Flowers and Florists

Eola Acres Florist and Gift Shop

Nurseries

Oregon Bulb Company

Olson’s Florist

Salem Bulb Company

Grocery Stores

Home Supplies

Home Service Oil Company

Northwest Natural Gas

Salem Tent & Awning Company

Whitlock’s Vacuum and Sewing Center

Launders

Legal Businesses

Key Title Company

VanNatta Public Relations

Music Stores

Newspapers

Capital Press Newspaper

Statesman Journal

Restaurants

Retirement Homes

SEDCOR

Infrastructure

Airport

Bridges

Buses and Auto Stages

Buses in Salem: 1927-1979

Buses in Salem: 1979-2001

Central Stage Terminal & Hotel Company 1921-1928

Courthouse Square

Railway

Chemawa Station

Origins

Railroad Depots

Salem Passenger Depot

Salem

Salem to Independence

Waconda, Hopmere, and Quinaby Stations

Ferries and Steamboats

Daniel Matheny V

Ferries

Steamboats

Streets and Streetcars

Places

Businesses

Community Institutions

Courthouse Square

Glen Oaks Orphanage

Heritage Institutions

Local Government

Reform School

Salem Downtown Historic District

- Franklin Building/Masonic Temple

- 109 Commercial Street NE

- 110 Commercial Street NE

- 120 Commercial Street NE

- 129 Commercial Street NE

- 135 Commercial Street NE

- 170 Liberty Street SE

- 174 Commercial Street NE

- 179 Commercial Street NE

- 188 Commercial Street NE

- 195 Commercial Street NE

- 198 Liberty Street SE

- 201 Commercial Street NE

- 216 Commercial Street NE

- 223 Commercial Street NE

- 223 High Street NE

- 240 Commercial Street NE

- 315 State Street

- 377 Court Street

- 429 Court Street

- 467 Court Street

- 508 State Street

State and Civic Buildings

Willamette University

People

Content Coming Soon!

Biography

Biographies

Featured Articles

Dr. S.A. Davis Comes to Salem, 1890

Heritage Center2023-09-18T11:08:54-07:00September 18th, 2023|0 Comments

It was likely a warm summer day when the steam locomotive huffed and hissed into the Salem railroad depot in 1890, and the travel weary, newly minted graduate of the American Medical College of [...]

Women Working on the Railroad in Salem

Heritage Center2023-06-15T18:10:49-07:00August 9th, 2023|0 Comments

The Women of Salem's Wartime Roundhouse Donna Beall at the Salem Roundhouse. Photo by Ben Maxwell. Published in the Capital Journal Friday, May 24, 1946. Ever since the arrival of Caboose 507 at the Willamette [...]

First Christian Church

WHC Research Intern2022-12-30T12:31:00-08:00December 30th, 2022|0 Comments

First Christian Church A.K.A. Christian Church Unless otherwise noted, information was taken from the booklet "First Christian Church, Salem, Oregon The Centennial Story 1855-1955" published by the church and a copy of which is [...]

Confluence

WHC Research Intern2022-10-28T09:19:09-07:00October 28th, 2022|0 Comments

Confluence LGBT Chorus Whether doing karaoke with your friends or being in the crowd of a concert, it cannot be argued that when singing and music are shared with others, a sense of joy [...]

Salem Pride

WHC Research Intern2023-02-24T11:13:11-08:00September 26th, 2022|Comments Off on Salem Pride

After the riot at New York City’s Stonewall bar in June of 1969 and the gathering that occurred the next year, many LGBTQ+ communities across the US slowly started to host their own marches. [...]

Nora Anderson

Heritage Center2022-08-25T16:11:07-07:00May 9th, 2022|0 Comments

Portrait of Nora L. Anderson. WHC Collections 1997.012 A major honor accorded to Nora Anderson during her lifetime was the dedication of the first bench in Bush's Pasture Park. In keeping with Anderson's [...]

About

The Salem Public Library sponsored the creation of the Salem History Project which is funded by a two year grant provided by the Library Services and Technology Act by the Oregon State Library, State administered Program, P. L. 104-208. Grant funding was awarded to the Salem Public Library of the City of Salem.

The Salem History Project takes an encyclopedia approach to providing access to Salem’s history of culture, events, institutions and people which has led our community into the 21st Century. While the web site is focused on historical information, there is the possibility that factual information may be modified or corrected over time and the City of Salem nor Salem Public Library can not attest to the continuing accuracy of information over the test of time.

Bibliographic information on the sources of the historic information were gathered and displayed on the web site to support other researchers who are interested in pursuing more information on Salem’s history.

Products to be produced through grant funding:

1. An Internet web site for general public access.

Grant funding provided wages for a part-time Project Coordinator and computer equipment necessary to design and maintain the grant products. A team of volunteer researchers is providing the research talent and focus to the development of the project.

Contact Information:

Salem History Project Coordinator

Salem Public Library

P.O. Box 14810

585 Liberty St. SE

Salem, Or 97309

503-588-6182

Email: library@cityofsalem.net

N.B. As of 2020 the contact information is no longer accurate

Technical Information:

The grant funds purchased a HP Net Server 60, Pentium III 600, 256 Megs of RAM. Operating software is Windows 2000 Server IIS 5. A Dell lap top computer.

Additional equipment included a digital audio recorder, Microteck ScanMaker 9600 XL scanner, Dell OptiPlex GX 100 computer work station with 254 MB RAM.

Credits:

Salem Public Library – Staff

Gail Warner, Library Director

George Happ, retired Library Director

Bob Miller, Executive Project Coordinator

Salem 2000 Encyclopedia Grant

Janice Weide, Library Reference Supervisor

Jane Kirby, Reference Librarian and Historian

Judy Jacobson, Reference Librarian

Abigail Elder, Reference Librarian

B. J. Quinlan, Youth Services Librarian

Marcia Poehler, Technical Support

Ann Scheppke, Reference Librarian

Salem History Project Coordinator

Monica Mersinger, Grant Project Coordinator

Grant Partner

Marion County Historical Society

Executive Director, Kyle Jansson

Project Historian

Project Steering Committee

Darlene and George Strozut

Susan Gibby

Sue Bell

Al Jones

Doug Houck

Joan “Toni” Meyering

Layne Sawyer

Craig Smith

Ross Sutherland

Alden Moberg

Kathleen Clements Carlson

Sue Morrison

Virginia Green

Burt Edwards

Paul Porter

Monica Mersinger

Jane Kirby

Project Artists

Eric Wuest

Sandi Cormier

Technical Team

Eric White

David Brown

Tom Bender

Jane Kirby

Sue Gibby

Virginia Green

Carey Lee

David Goodson

Bruce Fitchman

Ann Scheppke

J. Reyes Juárez Ramirez

Becky Clark

Jeffrey Sharp

Anna Short

Ann Scheppke

Contributors

Rod Stubbs

Melinda Woodward

Hugh “Tip” and Mary Ann Hennessey

Richard Lutz

Sybil Westenhouse

Rosanne Gostovich Royer

Wes Sullivan

Ronda Blacker

Phil Decker

Nancy Gormson

Shirley Herrmann

George Katagiri

Yvonne Litke

William Lucas

Richard L. Lutz

Al Jones

Darlene Strozuts

Kyle Jansson

Bruce Fitchman

Cynthia Harvey

With special thanks to:

Statesman Journal Newspaper

Oregon State Library

Oregon State Archives

Mission Mill

Deepwood Estates

Bush House

A.C. Gilbert Discovery Village

Elisnore Theater

c. 2005-2006

City of Salem Historic Planning Division

Oregon Community Foundation

Salem Public Library Advisory Board

During the 2022 transfer, the WHC opted to post many materials as they were written. These articles include a disclaimer notice indicating that they have not been updated since 2006.

If you think information on this site is in error, please email us or call 503-585-7012 ext 257, or fill out the form below, please include the link to the article in question!

Advisory Committee

Become a member of the advisory committee. We meet quarterly to review submissions and provide oversight of the content.

Submissions

Do you see a story missing? The WHC enthusiastically welcomes submissions of materials for inclusion on the Salem Online History Hub. In order to maximize accessibility, promote responsible scholarship, and provide institutional branding consistency the following standards and guidelines have been developed.

Topics

Materials should be related to a person, organization, place or event in Salem, Oregon. Topics related to the surrounding areas of the city of Salem (i.e. the history of agricultural in the Mid-Willamette Valley, history of the city of Keizer) may be included if it is clear from the article the connection to Salem’s past.

Inclusion

We are striving to create a site that is representative of all citizens from this city’s past and their varied experiences. We value, promote, and prioritize including a diverse stories and points of view and recognize that an unintentional lack of stories and scholarship within the body of work as a whole as a problem.

We recognize that the words we choose are important and can affect how people read and understand information. We will seek to use inclusive, and people-first language in all parts of the site. Inclusive language is defined as language that avoids the use of certain expressions or words that might be considered to exclude particular groups of people, especially gender-specific words, such as “man”, “mankind”, and masculine pronouns, the use of which might be considered to exclude women.5 People first language (PFL) is defined language which puts a person before a diagnosis, describing what a person “has” rather than asserting what a person “is”. It is intended to avoid marginalization or dehumanization (either consciously or subconsciously) when discussing people with a chronic illness or disability.6

We recognize that language is an evolving thing and that it can affect the reception of the information laid out in articles and scholarship overtime. As a web-based publishing platform we have the flexibility to be responsive to changes. We reserve the right to update language that may be considered offensive, out of date or not accurately representing the people and events described in articles.

Citations

We believe it is important for future readers to know what sources were consulted at the time of research and to take some guesswork out of fact checking. We ask that all submitted articles use academic citations in the form of footnotes inside the text for specific references to facts and assertions. We suggest using the Chicago Style Manual for consistency in footnote formatting. If general materials are consulted which result in a general, rather than a specific help to the researcher, a bibliography can also be provided, but is not required.

Article Formatting and Style

Illustrations

We encourage authors to seek out images to help illustrate their articles. However, we are bound by copyright restrictions and will not post images for which we cannot get written permission. At this point in time, we do not have a budget to pay for use of photos from other institutions. Writers are encouraged to ask WHC staff to check WHC holdings for appropriate images within the collections maintained by the Willamette Heritage Center. No photos will be posted without attribution to their original source material regardless of copyright status. Our goal is to include at least one illustration with each article.

Section Headings

In order to make materials as accessible as possible, we try to utilize tools of Search Engine Optimization (SEO) to make articles more findable on the internet. A big portion of this is the utilization of section headings within the text. All published articles will have the text body broken up into smaller sections with headings (rule of thumb about 300 words per section). Authors are encouraged to write their own headings. Articles submitted without headings may have them created by editors.

Voice

While we are excited about quality scholarship, we also know that our audience likes a good story that is easily readable. We are aiming for articles with a Fleisch-Kincade Reading scale grade of 70.0–60.0. We would also encourage authors to think about narrative and story in addition to the relating the facts.

Length

There are no length restrictions on the articles.

Primary Sources

The WHC values primary sources and making these materials as accessible as possible to individuals. Authors are encouraged to include transcriptions of original source materials in the text or as an addendum to the article.

Submission of Articles

Articles should be submitted in digital form, utilizing footnote citations to Kylie Pine (kyliep@willametteheritage.org) and Kaylyn Mabey (kaylynm@willametteheritage.org).

Author Attribution

All new articles will be attributed to their authors when posted and a date of posting will be stated.

Editorial Process

In addition to a member of the WHC staff, articles may be reviewed by an outside volunteer or member of an advisory committee. Reviewers may make grammatical corrections to the text and insert subheadings if not submitted by author. If significant changes to the content of the text are deemed advisable by the reviewer, the article will be sent back to the author with suggestions and asked to be resubmitted.

It is the goal of this site to remain accurate and current as now scholarship arises. The WHC staff or volunteers may choose to make notations or comments to original submissions in the future. Changes should be identified in the text.

If the author has a concern about editorial changes, they should submit them in writing to WHC Staff.

Oral History, Documentation and Privacy

If the author relies on sources that are not publicly accessible (private collections, interviews, personal recollections), we ask that that information be communicated through citations or in the text itself, while respecting the privacy of individuals potentially not a part of the writing or publishing process. We encourage authors engaging in interviews to consider conducting a formal interview and submitting it to be a part of the WHC’s oral history collection for future researchers. Please request information about guidelines for Oral History best practices. For informal interviews (those not recorded/transcribed), we would encourage transparency in communication with the narrator about the final use of the interview and a signed release form giving the WHC permission to publish their name.

Funding for this project was provided in part by the City of Salem.