What is the answer to the water pollution problem faced by the city of Salem?

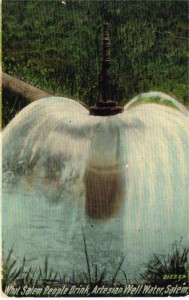

Photo Postcard showing artisian spring. c. 1920. Despite this postcard, most Salemites in 1920 got their water from the Willamette River. Photo source: 2011.006.0060.

Will it require tapping of a new source of supply to insure clean and wholesome drinking water?

No, this is not a modern editorial. This statement was published in 1928, in the midst of another Salem water crisis that rivalled today’s worries. It all started November 27, 1928, when Salem residents started to notice a “disagreeable” taste and smell to water flowing out of their taps.[1] The problem persisted throughout the month of December, with city leadership continuing to receive complaints as late as February 25th of the following year. [2] One columnist quipped that it was as if the water company had mixed up their pipes with the gas company, sending out gas instead of water.[3] A new joke started circulating: “By Golly, nobody can sneak up behind us with a bucket of Salem water and wash our neck and ears when we’re not looking – we’d smell ‘em coming.”[4]

Boiling didn’t help the smell or the taste.[5] Water company officials were quick to assure the customers that the water was safe and that the event was a natural occurrence. The beleaguered spokesman claimed: “The water supply is exactly the same as it has always been and the treatment is carried on in exactly the same manner. It is simply a condition that maintains each season in a varying degree, depending on the previous summer season. This disturbance is perfectly harmless and will not obtain long, as we are daily flushing our mains to get rid of it as rapidly as possible. Daily tests are made and these tests show the water pure and safe, more than meeting both state and United States government health requirement.”[6]

Assurances of the water’s safety didn’t make it any easier to drink or bathe with. Some editorialists suggested going out to the country and taking a jug along to help supply daily use needs.[7] Alternative water markets began to spring up. Enterprising individuals sold water from springs at Eola to thirsty Salemites, even offering delivery. “Hundreds of gallons have been brought to Salem by private parties for home consumption and as no relief has been forthcoming, a new enterprise has sprung up overnight with the commercial delivery of fresh water,” one paper reported while quoting the daily price of a gallon of water at 10 cents.[8] Despite efforts of the Chamber of Commerce to discourage downtown confectioners from advertising spring water (they feared it would cause panic or a bad reputation), sales were brisk.

The smell wasn’t just a problem for daily life. Industry suffered as well. Canning was a huge part of the Salem economy and the foul smell meant they could not put up food for commercial sales. One Capital Journal editorialist satirically suggested that the city start a new industry. Citing many civilizations who used algae as food and for its curative effects he suggested: “…here is a great opportunity for our Chamber of Commerce to foster a new industry, with the raw material delivered by faucet. If our canneries cannot put up fruit, they can can algae as breakfast and health food and so make Salem famous, for the algae supply seems unlimited. If the Water company cannot can the algae, the rest of us can.”[9]

In testimony given in April 1929 to a city committee, officials for the Oregon-Washington Water Company attributed the cause of the smell to natural forces –a long dry summer followed by cold snap and quick rise of water meant an increase in organic matter and organisms which couldn’t be filtered out quick enough and a buildup of crenothrix (defined in his testimony as iron algae) within the iron pipes adding to the problem.[10] Scientific explanations were discredited by some in the community. Comments aired at one public meeting suggested that “the average boy who has slaked his burning thirst from a roadside puddle is just as sure as to what ails the water as your cocksure scientist with his befuddling new words.”[11] Or a little more plainly expressed: “What’s wrong with the water, doggone it, is that it tastes bad and smells bad. We figured that out without any outside help…”[12]

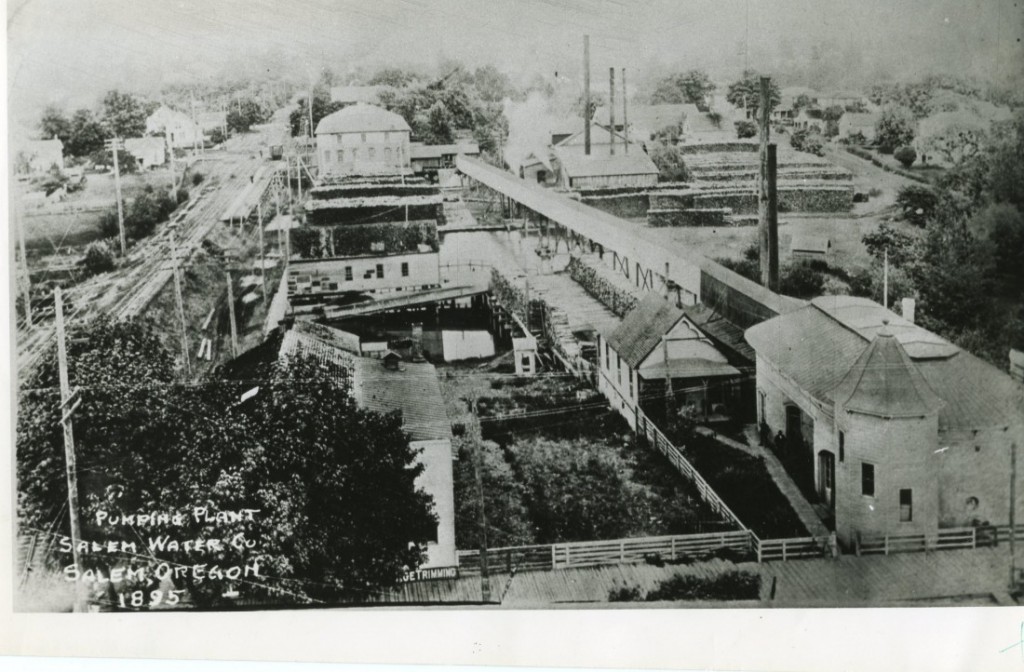

This wasn’t the first occurrence of the problem. Similar smells were reported in 1925,[13] but this was the by far the worst case and it prompted Salemites to reconsider much about the way they got their water. Up until this point in time, water service within the city was principally supplied by a private water company that pulled its water out of the Willamette River by means of a pumping plant located on the southeast corner of Commercial and Trade Streets. Improvements had been made in years past to extend the intake valve across Minto Island to the fresher flowing water beyond the slough and filter cribs were installed to help with water quality, but these were not enough for the present problems.

Water pumping plant that pulled drinking water out of the Willamette for us in Salem. Located on the S.E. corner of Trade and Commercial Streets. Photo Source: WHC 2012.049.0084.

Suggestions for improvements were plentiful – from the serious to the sarcastic. Everything from setting up a new and parallel drinking water system fed by wells in the country hills and keeping the current system for irrigation[14] to forcing the water company to supply every customer with a still to allow them to purify their own water. Some even suggested a boycott until complaints were addressed.[15] Still many others advocated looking to the mountains for a fresh supply of water [16]– and it was this course that would eventually be acted upon, although it would take several more years.

By 1930 the people of Salem were pretty fed up with the water situation, and voted to make the water system public,[17] but the wheels of negotiations would move very slowly. The city did not take over the system until 1935[18] and the dream of mountain water would not come to fruition until 1937.[19]

I think the citizens of Salem past would be very sympathetic to our current problem.[20] I guess we can consider ourselves lucky — at least the water doesn’t stink!

This article was originally written for publication in the Statesman Journal, July 1, 2018 by Kylie Pine. It is reproduced here with citations and expanded information for reference purposes.

Want to Learn More?

For a good overview of the history of Salem’s water system and quest for mountain water, check out Frank Mauldin’s Sweet Mountain Water. Salem, Oak Savannah Press, 2004.

Sources Cited

[1] “City’s Water Troubles Aired.” Capital Journal 29 April 1929.

[2] “City’s Water Troubles Aired.” Capital Journal 29 April 1929.

[3]Upjohn, Don “Sips for Supper.” Capital Journal 12 Dec 1928. Page 1. “We’ve been wondering if the water company has made a mistake and run its pipes into the gas company’s tank instead of into the river…A man to enjoy the water these days must have a most fastidious taste—or a nose mask.”

[4] “Urges Well Water for Salem.” Capital Journal. 29 Dec 1928, pg 1.

[5] Oregon Statesman. “Gibson T. White.” 19 December 1928

[6] “Tests Attest Water Purity.” Oregon Statesman. 13 Dec 1928. Pg 3.

[7] Ferrey, Martin F. “Forum”Capital Journal. 29 Dec 1928 pg 6

[8] “Eola Water Finds ready market Here.” Capital Journal. 31 Dec 1928 pg 5.

[9] “For a New Industry.” Capital Journal (Salem) 07 Feb 1929. Pg 4.

[10] “City’s Water Troubles Aired.” Capital Journal. 29 April 1929. Quoting the testimony: “The cause, he said, was an organic content brought on by conditions of the summer and fall of 1928. A long dry season, he explained, reduced the river water volume to a low stage. As a result there was more than the normal growth of organic matter in the river bed, while small tributary streams were quite full of it. In the early fall a cold spell killed the organic matter. This was followed by a thaw and a small freshet that raised the water and caused the river to carry an excessive amount of the organism, resulting in stained water and a disagreeable taste. AT the time, he said, the raw water was being pumped from the main stream on top of the filter bed, and the amount of organic matter was so great that the filter was unable to remove it.

Since that time, he continued, an iron algae, or crenothrix, which had resulted from the organic content of the water, had become attached in the mains. Treatment for this is chlorination and constant flushing. Flushing, he said, is being done constantly, oftener than is required by sanitary engineering and results, he claimed, have been very beneficial. Little or no complain has since reached the company, he said. The most modern type of liquid chlorinator has been installed at the pumping plan.

[11] Stills Seen as Cure for Dirty Water.” Capital Journal. 31 Dec 1928 pg 1.

[12] “Sips for Supper.” Capital Journal 10 Jan 1929 pg 1.

[13] Capital Journal. 4 Aug 1925 pg 5

“Officials of the Salem Water Company are still undecided as to the reason for the peculiar taste that has been noticed in the drinking water, it was stated this morning by Chas. A. Park, president of the company. When the taste was first noticed it was suspected by company officials that it might be due to algae, a minute vegetable organism that sometimes gets into drinking water. Not definite information was available at that time, however and none is available now. Mr. Park stated that the reservoir through which the water passes is cleaned out about once every three or four weeks.”

[14] “Pure Supply Near at Hand Judge Holds” Capital Journal 29 Dec 1928 pg 1.

[15] “Stills Seen as Cure for Dirty Water.” Capital Journal. 31 Dec 1928 pg 1. Two suggestions for forcing improvement of Salem’s water supply were advanced in the deluge of complains and ideas that are being heard on every hand relative to the existing situation by Louis Lachmund, former mayor, who during his administration vetoed and ordinance for purchase of the water supply system by the city.

“Let the water company supply all of its customers with stills with which to purify their drinking water,” said Lachmund. “The supply from the pipes will do in an emergency for bath and irrigation purposes, but it is not fit to drink.”

“Also, if the people of the city will get together and refuse to pay for this dirty water they will get remedial action on the part of the water company. The company is required to furish pure water, and if the people refuse to pay for this stuff they are getting I cannot see where the company could force payment.”

[16] Stills Seen as Cure for Dirty Water.” Capital Journal. 31 Dec 1928 pg 1. “Eventually Salem must have municipally-owned mountain water,” writes R.A. Harris to the Capital Journal. “Nothing less will satisfy the reasonable demands of pride and progress and nothing less should.”

[17] “Details of Water Plant Purchase are now Up to Council.” Oregon Statesman. 18 May 1930 pg 2.

[18] Mauldin, Frank. Sweet Mountain Water: The Story of Salem, Oregon’s Struggle to Tap Mt. Jefferson Water and Protect the North Santiam River.. Oak Savannah Publishing, 2004, pg 45

[19] Mauldin, Frank. Sweet Mountain Water: The Story of Salem, Oregon’s Struggle to Tap Mt. Jefferson Water and Protect the North Santiam River.. Oak Savannah Publishing, 2004, pg 57. See also Souvenir Cup for First Drink of Salem Mountain Water. Water Dedication held October 30, 1937 at 2:00 pm WHC Collections 2014.082.0203.

[20] Beginning in May 2018, elevated levels of cyanotoxins in the city’s drinking water prompted advisory warnings for vulnerable populations served by the city’s water system.

Leave A Comment