Oregon Played a Vital Role in the History of Domesticated Turkeys

For many, Thanksgiving is synonymous with turkey. We rarely consider the history of our food products, but turkey is a completely North American bird with a strong connection to Oregon and the Pacific Northwest.

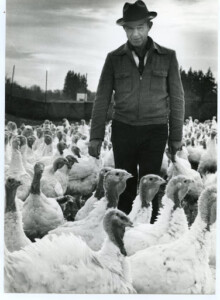

At one time, Oregon produced 30% of the West Coast supply of turkey. But, several years ago, the Oregon turkey industry–which, at its height, produced nearly 3 million birds annually–ceased to exist. This was due to a bankruptcy of Oregon’s primary turkey processor, brought about in part by a recall of about 70,000 birds just before Thanksgiving. While this signaled the end of commercial turkey production in Oregon, a few small producers continue to produce birds for local markets and many Oregon customers.

The modern commercial turkey has its roots in Oregon, where farmers played a dominant role in its development. Earliest records show turkeys in Astoria in 1813, and that turkeys were on many Oregon farms by 1846. Prior to the ’20s, turkeys were a farm sideline with the bronze turkey as the standard.

Many brought their birds to various shows for premium money and to sell breeding stock. During this time, Ward Cockeram, a turkey grower from Oakland, developed his “blackbirds” for meat production. In addition, Oregon producers Herman Odell and Joe Kupetz, as well as R.D. Mitchell from Washington, also were selecting for body size.

Then, at the Portland International Livestock Show, Jesse Throessell from Bri-tish Columbia showed his “Sheffield bronze” turkeys. The Oregon and Washington growers were impressed by these birds, bought stock, and bred it with their birds.

It was the ingenuity of Oregon and Pacific Northwest turkey producers in the 1920s and ’30s that made the turkey industry what it is today. Even though our Oregon turkey industry is gone, the history of Oregon’s influence on the industry nationwide lives on.

Origin of the turkey

The bird that we call the turkey is, basically, a North American pheasant or grouse. It is native to the eastern and southeastern United States and into Mexico. It is one of the only North American native animals (certainly the only bird) to be domesticated into a major-production agriculture animal. There are two species, turkey and ocellated turkey–with the latter native to the jungles of Mexico.

The U.S. produces about 280 million turkeys annually, with consumption of about 18 pounds of turkey per person per year. How did we get to where we are today in the turkey industry from the wild game bird of the southern United States?

The Aztecs first domesticated the turkey in Mexico some time before A.D. 700. In their conquest of the New World, Columbus and the Spaniards found domestic turkeys in Central America in the 1500s. In one of his later trips, Columbus was given what was thought to be a turkey by native Hondurans in 1502. However, the first confirmation that turkeys were taken to Europe was in 1511, when they were introduced to Spain.

After nearly 100 years in Europe, domesticated turkeys sporting their new colors were taken with settlers back to the New World in the early 1600s. Evidences of domestic turkeys has been found in Jamestown in 1607, and Massachusetts in 1629. Since turkeys were native to the New World, and wild turkeys existed near farms set up by the settlers, the native birds crossbred with the domestic European varieties. The crosses took on the color of the native eastern turkey (bronze), and many were larger in size than the European varieties.

This is what graces our holiday tables and sandwiches today!

Written by James Hermes. Mr. Hermes is a poultry specialist with the Oregon State University Extension services.

Bibliography:

Statesman Journal newspaper, Business pages, Agriculture column, November 11, 2001

This article originally appeared on the original Salem Online History site and has not been updated since 2006.

Leave A Comment